“Language is not just a social phenomenon but also a materialized tool that is used to legitimize one’s socioeconomic class, political status, racial and ethnic identities, and gender.” – Jina E. Kim

A close examination of countries who have undergone the painful, often destructive process of imperialism shows that there is no single tactic employed by the colonizer – and while physical, sexual and educational violations are often given the most attention, the impacts and legacies of linguistic imperialism cannot be disregarded. Linguistic imperialism is defined as the transfer of a dominant language to other people, mostly from the imperial power to the affected peoples. This often leads to language-based discrimination against native speakers, as the colonial language is attributed more power and privilege.

This article aims to show the similarities between the processes used by Canadian and Japanese colonial forces alike, and how this strategic linguicism continues to affect Indigenous and Korean communities today. By examining the historical policies and legacies of linguistic assimilation in both Indigenous communities in present-day Canada and Korea, we hope to provide a deeper insight into the necessity of protecting language in order to preserve the existing diversity of cultural identities.

The Indigenous Experience under Canada’s Policies of Assimilation

Canada is often celebrated as a model for progressive politics and multicultural diversity by the international community, and although this reputation is for the most part justifiable, it obscures social injustices that the Canadian government has inflicted upon its Indigenous peoples.

When discussions regarding linguistic conflict in Canada arise, the narrative is often framed through the lens of the English-French polarity – two linguistic rivals contending for cultural recognition. This lens ignores the diversity of Indigenous languages that pre-date both the presence of English and French on the continent . This false dichotomy is a product of centuries-old language policies enacted by the Canadian government, specifically targeting the suppression of a rich heritage of Indigenous languages and culture.

History

The contemporary state of Indigenous languages in Canada can only be understood by looking back on the power dynamics inherent to the imperial project and their influence on Indigenous culture. One of the virtues of Canadian society is its inclusion of multiculturalism in its Charter of Rights and Freedoms,however, Section 27 of the Charter makes no mention of the unique heritage of Indigenous peoples. It treats Canada as though it were a blank-slate with no pre-existing identities.

The Bilingualism and Multiculturalism Acts of the late 60s and early 70s reinforced racial and linguistic hierarchies that had privileged English and French over Indigenous languages as the only legitimate forms of Canadian identity. Prior to 1988, all new Canadian immigrants were expected to conform to a Western-European, English-Speaking way of life. Assimilation and conformity are nothing new to Canada; in many ways, Canada was founded upon them.

Laura Davis, a legal student at McGill University and student coordinator of Indigenous Initiatives, argues that ‘immigrant languages’ in Canadian policy are often categorically distinguished from English and French, the two official languages. She points out that this kind of distinction is inherently problematic because it “erases the fact that English and French are also immigrant languages” to the Canadian territory. Canadians have been socialized to think of English and French as the only authentically Canadian languages, further enforcing the notion that Indigenous languages are not only lesser than, but illegitimate. While multiculturalism seemingly encourage diversity, it also sets the standard for the recognition of the cultures within Canadian society worthy of respect: the explicit exclusion of Indigenous languages and cultures underscores their value in the eyes of the Canadian government.

Although many newcomers to Canada have fallen victim to assimilatory policies, Indigenous peoples have perhaps been the most directly affected. In the 19th century, the Canadian government saw Indigenous peoples as an “Indian Problem” that could be resolved through eliminating “Indianness”. According to the Indian Act, Indigenous peoples that met the minimum citizen requirements – education, literacy, and Western moral character – were granted the opportunity to earn full citizenship through enfranchisement. Enfranchisement meant that they would earn the right to become a part of the Canadian citizenry – vote, purchase alcohol, and purchase land – at the cost of their communities and culture. Enfranchisement was a process by which Indigenous peoples would give up their ‘Indian Status’ under the federal government, and effectively give up their identities.

The Linguistic Legacy of Residential Schools

While some contend that Canada’s goal to eliminate “Indianness” was rooted in a misguided form of paternalistic concern for Indigenous peoples, systemic assimilation is always ingrained in a sense of cultural superiority and ethnic prejudice. In the 19th century, along with enfranchisement under the Indian Act, the Canadian government instantiated a policy entitled “aggressive assimilation” which sought to establish residential schools. These schools were government funded institutions that aimed to teach Indigenous youths English (as well as to a lesser degree, French) and have them adopt Christianity. By 1931, at the system’s peak, there were approximately eighty residential schools in operation across Canada, with the last one closing its doors as recent as in 1996.

Students in residential schools were forbidden from speaking their native languages and practicing their traditions. If caught, they were met with harsh punishment. Cultural re-education in these schools was accompanied by sexual abuse, substandard living conditions and the long-term separation of Indigenous students from their families. Residential schools focused on linguistic education because the government recognized the strong connection between language and culture; by erasing language, they could dissolve cultural identities. Many Indigenous peoples’ cultural histories across Canada depend on on oral transmission, so without intergenerational transmission, they are at risk of being lost.

The violence and severity of linguistic re-education in residential schools meant that even when students returned to their homes over the summer, they were incapable of communicating with their family members and community Elders, who only spoke their native tongues. The Canadian government used language as a weapon to break Indigenous communities by eradicating their linguistic heritage and severing lines of communication with their peoples.

Historical and Current Implications

According to Statistics Canada, Canada is home to sixty Indigenous languages shared amongst twelve overarching families including ten First Nations, the Inuit, and the Métis. These languages are spoken by nearly 229 000 Indigenous peoples who rely on them, not only to communicate with members of their community, but also to connect to a deep cultural heritage that extends thousands of years back. Despite the resilience that these communities have demonstrated over time, amidst colonial oppression and the grassroots efforts by Indigenous Nations to keep these languages alive, the UNESCO Atlas of the World’s Languages has confirmed that only Cree, Inuktitut and Ojibwa are among those Indigenous languages in Canada that currently have enough speakers to be sustained organically.

In 2007, the United Nations instantiated the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) which states, under Article 13, that Indigenous peoples have “the right to revitalize, use, develop and transmit to future generations their languages”. The resilience of cultural heritage in the face of colonial oppression is a human right that Indigenous communities are entitled to. However, over the past centuries, the linguistic hierarchies entrenched within Canadian society have both institutionally and socially threatened this freedom.

The Korean Colonial Experience under Japanese Imperialism

History

From 1910 to 1945, Korea underwent colonization by imperialistic Japanese forces and became a Japanese colony. Due to its geographic proximity to Japan, as well as its underlying political potential as an annex to the growing Japanese occupation of East and Southeast Asia, Korea was targeted as an extension of Japan. It underwent thirty-five years of “Japanization”: attempts to make Koreans Japanese, notably through both subtle and obvious acts of linguistic imperialism. Despite the fact that more than a century has passed since the beginning of this colonial relationship, the legacies of linguistic imperialism still continue to create rifts in the economic, political and social ties between the two countries to this day.

The Korean language has a unique history: while the spoken language has been circulated for thousands of years, its written counterpart was created by King Sejong (세종대왕) in the 15th century. Nonetheless, between 1450 and 1910, written Chinese (한자) and an adapted form of spoken Chinese was popular thanks to the influence of the nobility, who considered it an indicator of elite status and higher education.

It wasn’t until the colonization of Korea in 1910 that Koreans began promoting Kugo (국어) as the Korean language in order to create a unified identity, as a part of the “rise of nationalism in response to foreign aggression”. The ‘Joseon Eohakhwe’ (Korean Language Society) was a group of scholars who initiated the nation-wide struggle for the promotion of the Korean language. However, as Japanese imperialist tactics diversified and intensified in order to eradicate the use of Korean, the Society shifted its focus from the promotion to the preservation of the Korean language. As the Society faced mounting opposition from the colonial government which made learning Japanese a mandatory part of the curriculum, the study of Korean became ‘voluntary’ in schools in 1938 per the newly revised Korean Education Statute (which was re-established by the colonial government).

By 1941, the imperial government had succeeded in removing Korean completely from the curriculum and banning its instruction, thereby implementing a fully Japanese language education system. Soon after, the Korean Language Society was forcefully disbanded in 1942, with many of its members becoming incarcerated or killed by the Japanese government.

Process of Linguistic Imperialism

Japan’s imperial government made a crescendo effort to achieve complete linguistic dominance in Korea in a matter of a few decades. This process entailed the following three strategies: first, the native legislature was modified to accommodate the demands of the colonial government. The continuous change of the Korean Education Statute, which eventually banned the teaching of Korean in schools by 1943, is one example of the colonial government editing the legislature to fit its own interests. Indoctrination also played a very significant role in Japan’s movement to achieve complete “Japanization”, and that propaganda represented a crucial element of the colonial curriculum’s goal to render Koreans subservient and make them loyal subjects to Japan, in particular to its Emperor Ten’no.

The second procedure was a result of the first: linguistic stratification, or the categorisation, division and distinction between the indigenous language and the colonizer’s. The colonizer’s language was attributed high status and power, thereby disempowering the native language and speakers and establishing an even more unbalanced power dynamic between the colonizer and colonized.

Finally, the third procedure, “linguicism,” consisted of the complete elimination of the local tongue. In order to achieve this linguistic homogeneity, the dominating force employed methods of linguistic oppression such as the “carrot and stick approach”, where the use of the native language invoked punishment from the colonial power while becoming fluent in the colonizer’s language was rewarded with the promise of higher economic status, more employment opportunities, and equal treatment. For Korea, this even included the forceful change of Korean last names to Japanese names of relatively similar meaning.

Ultimately, this process of linguistic surveillance has had serious implications in countless colonized regions around the world, including native language decline, the creation of pidgin or creole languages, as well as language genocide.

So what sparked this frenzied race to colonization? Imperial Japan, having come to the realization that, to be a modern power was to be a colonial power in the 20th century, began its conquest of colonizing Asia, mimicking similar Western scrambles at that time. Especially in East and Southeast Asia, it attempted to establish a stronger Asian identity (Japanese Pan-Asianism) and a more significant global presence in the increasingly Western-dominated world, thus “protecting” the colonized countries from “Westernization”. Therefore, it was necessary for Japan to make its colonies “Japanized”: a supportive colony which embraced its new identity would prove helpful to the imperial government’s colonial efforts by providing labor, intellectual support, and economic benefits through the exploitation of its land and peoples.

Historical and Current Implications

Language is often a gleaming indicator of social issues and social change, and is a crucial part of one’s cultural identity. That being said, the implications of establishing linguistic dominance by taking one’s language away and enforcing another in its place can be negative and long-lasting.

To demonstrate this point, Hiroyuki uses the example of Micronesians islanders, who also experienced linguistic imperialism under colonial Japan. She explains that some of the older Micronesian islanders still have a positive view of Japan, especially of the former Emperor Ten’no. However, she also discusses the negative legacies of such colonial policies amongst the Micronesians: the native Micronesians suffered racial prejudice and were labeled as inferior, lower-class citizens despite many having achieved fluency in Japanese. They experienced an identity crisis, with many saying that they “felt ashamed of identifying themselves”.

The elimination of the existing tongue was crucial to Japan’s colonial efforts because language is a direct representation of the social aspects of a community: a country’s culture, traditions, mindset and even spirituality are argued to be tied to its language. Therefore, changing the language of a community by enforcing the language of the colonizer would facilitate the transition into eventually adopting the colonizer’s traditions, cultures and beliefs. And even for those colonial subjects who accepted the new changes and sought to achieve an elevated status by “becoming Japanese” and becoming fluent in Japanese, they soon discovered that the promises of inclusion made by the colonial government would never be fulfilled.

This offer of inclusivity and the subsequent lack of fulfillment was one of the propellants of active Korean opposition against Japanese imperialism. Many scholars have also made the connection between the Korean language and identity, as language preservation and promotion movements were a crucial part of the independence movement. To many Koreans today, the “soul and spirit of the nation” is embodied in Korean, which had been targeted by colonial Japan to achieve its imperialist agenda, but soon became a tool of resistance and a symbol of independence.

Conclusion: A Comparative Lens

In the way that Indigenous peoples in Canada are still experiencing the effects of its colonial history today, Korea is also still recovering from the damages of colonial oppression. The legacies of colonialism can be seen in the ongoing conflicts regarding historical accountability, land ownership and the Korean population’s generally negative attitudes toward the government of Japan today.

A conflict of ethnic identities existed for a long period until active involvement from civil society refined and established Hangul as Korea’s official written language, as Japanese was perceived as a “sign of oppression and legitimacy”. In other words, the only way to escape the clutches of colonial repercussions was to become as dissociated from Japan as Korea is today.

Similarly, relations between Indigenous peoples and Canada are still fraught with tension regarding socio-economic inequity, issues over sovereignty, and the lack of political accountability to Indigenous communities, all of which are enduring consequences of an attempted cultural genocide.

Forcible assimilation is not a mechanism of national cohesion, it is a weapon of erasure. Canada’s linguistic policies are emblematic of the degree to which the federal government has never thought of Indigenous peoples as members of a diverse Canada, rather, they were treated as subjects of an arbitrarily-imposed colonial regime. For Indigenous peoples in Canada, language is a vehicle through which to connect to a collective past that resists the colonial oppressors.

Although Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s federal government has rhetorically made attempts to demonstrate solidarity with Indigenous peoples across Canada, his resolve to push forward with a pipeline that cuts across treatied Indigenous territories sends a very different message. Likewise, despite efforts at repairing the estranged relationship between Japan and Korea, not much progress can be said to have been made: the ongoing trade conflicts, issues regarding comfort women, Japanese textbook debates and Korean restrictions on Japanese imports only prove this point. Park claims that this is due to the “emotional scars left in the hearts of Koreans”, as language is not only reflective of social change and the history of the peoples, but is also a crucial manner of legitimating one’s “socioeconomic class, political status, racial and ethnic identities, and gender”.

Although these policies of linguistic imperialism are no longer formally in place in either Canada or Korea, the reach of their imperial legacies can still be felt to this day and symbolize a weighty reminder of a history of oppression in both countries.

Edited by Naya Sophia Moser

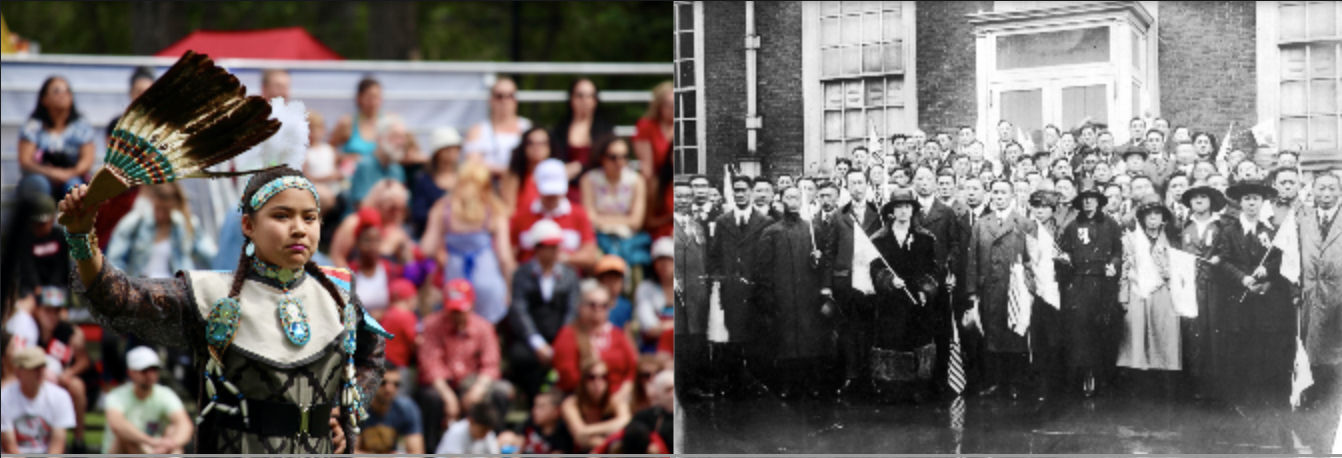

Photo credit (left): “Jingle Dress Dance Wave” by JMacPherson. Published 1st of July, 2018. This work was sourced under a Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0) license. No changes were made.

Photo credit (right): “Korean Independence League, Philadelphia 1919” by University of Southern California. Published April 2019. This work was sourced as public domain. No changes were made.

How wonderful that you explain how language is so important to learn about social issues and change and have a cultural identity. I am going to start teaching children at home this year and I’m planning my history curriculum. I will find a reputable imperialism game for this as well.