Here are some of the most recent headlines of the New York Times at the writing of this piece: Trump Uses Justice Dept. Speech to Air Grievances Against His Enemies, ‘People Will Die’: Trump Aid Cuts Threatens Refugees’ Survival, U.N. says, and Democracy Dies in Dumbness. It goes beyond saying that the 2024 United States elections have profoundly uprooted both international and domestic confidence in the world order and personal security. As the third month of President Donald Trump’s second term begins, the cause of the matter must be unveiled to even attempt to navigate a turbulent future ahead for the world. As a leading hegemon for a major part of the two past centuries, the future of the U.S. is intrinsically tied to that of the rest of the world. It is not the only country currently experiencing a political turnover, such as with the rise of the right wing in Germany, the fiery debate between parties in Brazil, or polarized nationalistic ideals in India. Thus, it provides an important case study of the decline of civil society, which sets important checks and balances against governments too far from their own people.

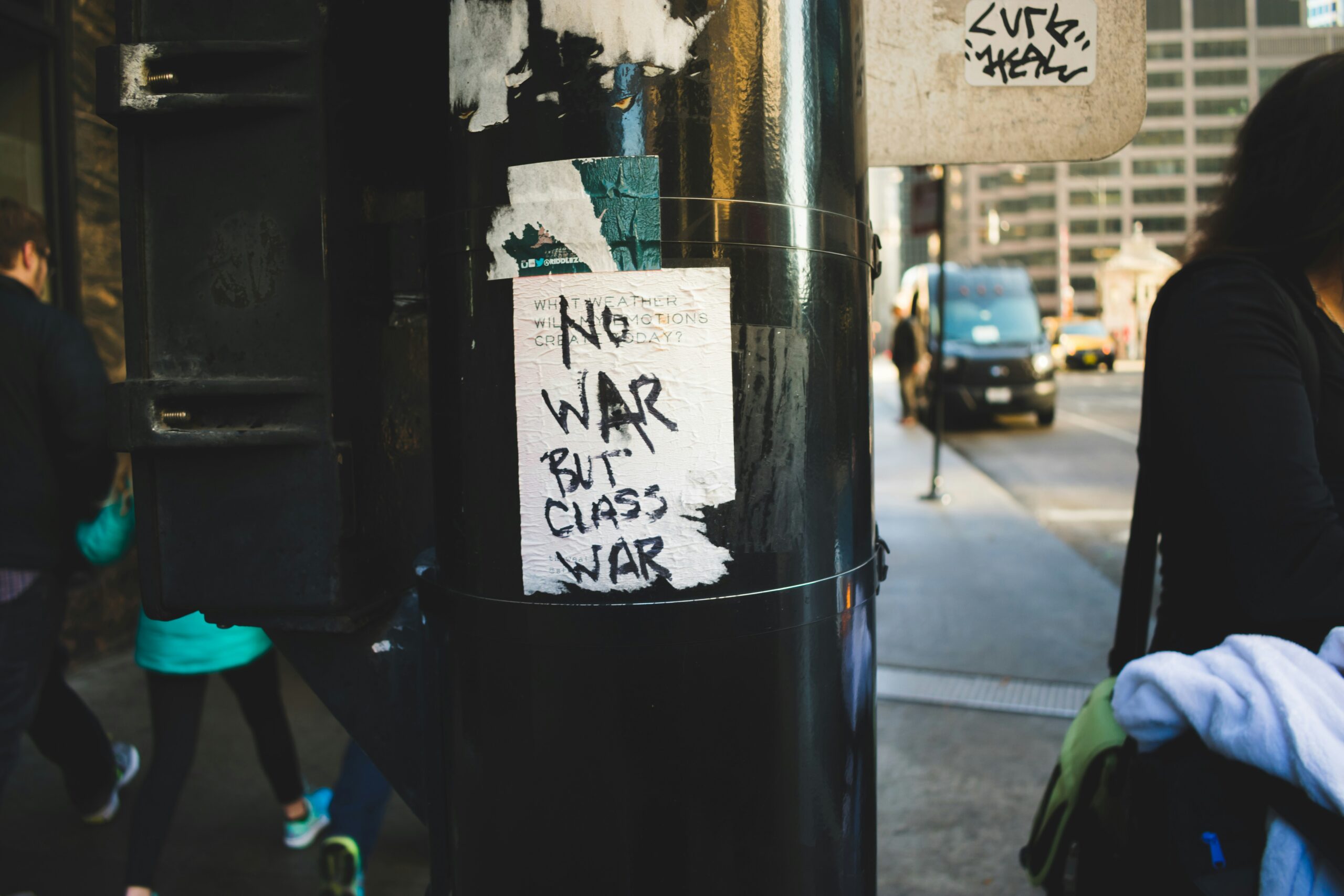

Any self-respecting study must begin with a hypothesis. Mine can be summarized in two words: divisive politics. In 2003, Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders introduced the concept of divisive politics to high school students. In a nutshell, divisive politics entail that instead of rallying people under a common issue (e.g., free healthcare and education), a political party will seek to divide voting blocs under key issues (e.g., race, gender, gun laws, sexuality, etc.). These are also commonly associated with dog whistle politics, which involves the political spread of a certain stereotype. Ultimately, such a strategy distorts national priorities while segregating civil society by sowing hate and fear. In Bernie’s words, “the middle class [votes] against its own interests and the rich go laughing all the way to the bank.” Moreover, the omnipresence of mass media and communications cannot be underestimated within this phenomenon. For example, over 54% of American adults rely on social media for a minimum of information purposes. This can engender echo chambers, which are adequately described as “bounded, enclosed media space that has the potential to both magnify the messages delivered within it and insulate them from rebuttal.” All things considered, from the strong conservative backlash in the 1980s to the current political landscape, divisive politics have played a key role in determining today’s headlines.

So, what happened? While it is impossible to capture the full complexity of American extremism and conservative backlash within one article, several historical developments are particularly relevant to understanding the roots of contemporary divisive politics. In 1971, Lewis Powell introduced a memorandum entitled Attack on American Free Enterprise System, which, by and large, sought to insert the business community into U.S .politics. Consequently, a handful of extremely wealthy individuals began to fund conservative think tanks. The neoliberal interests of the business class, an endless amount of accumulation, free of governmental shackles, were now embedded in the fabric of American society. As the next two decades progressed, Ronald Reagan took over the political stage and elevated the conservative platform, using dog whistle politics. By the time George H. W. Bush campaigned, bolstered archconservatives threw their support to him and his promise to continue what Reagan had started. Bush delivered: by taking a page from Reagan’s playbook, he essentially gave a new flair of reality television to U.S. elections by attacking, demonizing, and marketing his opponents as anti-patriotic villains, also through the use of dog whistles. These dynamics estranged both parties and voters, thus fueling divisive politics. One of the latest developments we shall consider is the 2010 ruling of the Supreme Court in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission. This decision essentially removed governmental regulations allowing wealthy donors to fund electoral campaigns. Businesses, corporations, and billionaires could now exert enormous political influence by puppeteering willing candidates. A recent example is Elon Musk’s political action committee for the support of Trump; Musk has individually donated over 260 million U.S. dollars to the organization from April to December 2024, as well as several tens of thousands of U.S. dollars to other Republican state parties. Gerrymandering, the process of manipulating electoral boundaries to influence results, also remains a common problem during elections, with only 1 out of 10 districts being truly competitive in elections. American interests are consequently split between two ends of the spectrum, and this inherently unjust political and social system remains fueled by division.

Both Trump’s campaign and his first months in office are unprecedented in U.S. history. He has exerted the power of divisive politics over both the legislative and judicial branches of government, thus concentrating his individual ideals within the executive branch insofar as he can stretch its power. His first days in office are characterized by his pushback against transgender people (gender/sexuality), DEI and deportations (race), and the ‘woke’ movement (civil society). The harnessing of mass media with his billionaire accomplice Elon Musk was, and is a critical strategy. Social media algorithms and news outlets can be manipulated to spread a divisive message to an already polarized population. Indeed, if civil society is led by principled beliefs and human rights values, then the prime interest of the businessman is in danger. If the billionaire is made through the exploitation of labour for endless accumulation of capital, then he is inherently against the civil society that protests his methods. Moreover, if marginalized voices are muted, then the billionaire can freely engage in what David Harvey calls accumulation by dispossession, in other words, making the rich richer, and the poor poorer. The parts of civil society that do profit from this status quo can further channel their interests through a political opportunity structure, which is engendered when political parties and social movements find common cause. When government policy only reflects the interests of a specific group, it inevitably alienates other factions, contributing to social and political fragmentation.

Indeed, the power of the people cannot be underscored enough, especially when a democracy is staring at a precipice. Scholars drawing on social movement literature and social developments of the past decade have posited that political leaders might perceive civil society as a threat to government authority. Civil society is commonly defined as a process through which individuals and groups can challenge and argue with the status quo or with each other. It can shape new opinions and provide a vehicle for action. Leaders subsequently cut down funding to impede these organizations. Without the means to frame a call to action message, individuals within a bipartisan system are increasingly susceptible to falling into a message of divisive politics. Indeed, if the government only cuts down on the civil society that opposes it, then it can elevate the opposing side, which suits its interests. For example, Trump has been attempting to shut down USAID, which is a tremendous blow to civil society and transnational networks. His 2025 plan also hints at his potential goals: disassembling civil society and governance, and instead inserting his archconservative, unshakeable supporters. The nomination of Pete Hegseth as secretary of defence is but one example. Furthermore, hurting individuals leading civil causes deters civil society from using its collective power, such as the recent unlawful arrest of Mahmoud Khalil, a leader of student protests for Palestine. Thus, governance becomes an increasingly privatized endeavour, led by a class of wealthy businessmen who stay out of the crossfire by sowing divisive messages within the masses and putting a gun in their hands, all while claiming to serve their interests — in reality, the broader population’s interests are united, yet remain distant from those of the 1%.

Global civil society is a vulnerable thing. Such a frightening movement in the United States will undoubtedly have repercussions on the world order; the headlines which introduced this piece are a small sample of the emotional and physical violence which has already been enacted in foreign countries and on American citizens. Additionally, if the United States was once seen as a pioneer of democracy and freedom, then any society might slip and fall the same way. It is thus crucial that we understand, as humanity, who and what tells us we are divided, before letting history repeat itself.

This is an article written by a Staff Writer. Catalyst is a student-led platform that fosters engagement with global issues from a learning perspective. The opinions expressed above do not necessarily reflect the views of the publication.

Edited by Zoé Pelen

Amélie Garneau-Daigneault is currently in her third year at McGill University. She is completing her bachelor’s in international development studies, along with minors in gender studies and history. Amélie is especially interested in researching health disparities and the global transmission of diseases. Moreover, she examines the cultural and social consequences of global health and war. Amélie aspires to attend law school after her B.A. and to apply her learnings to engage in international law.