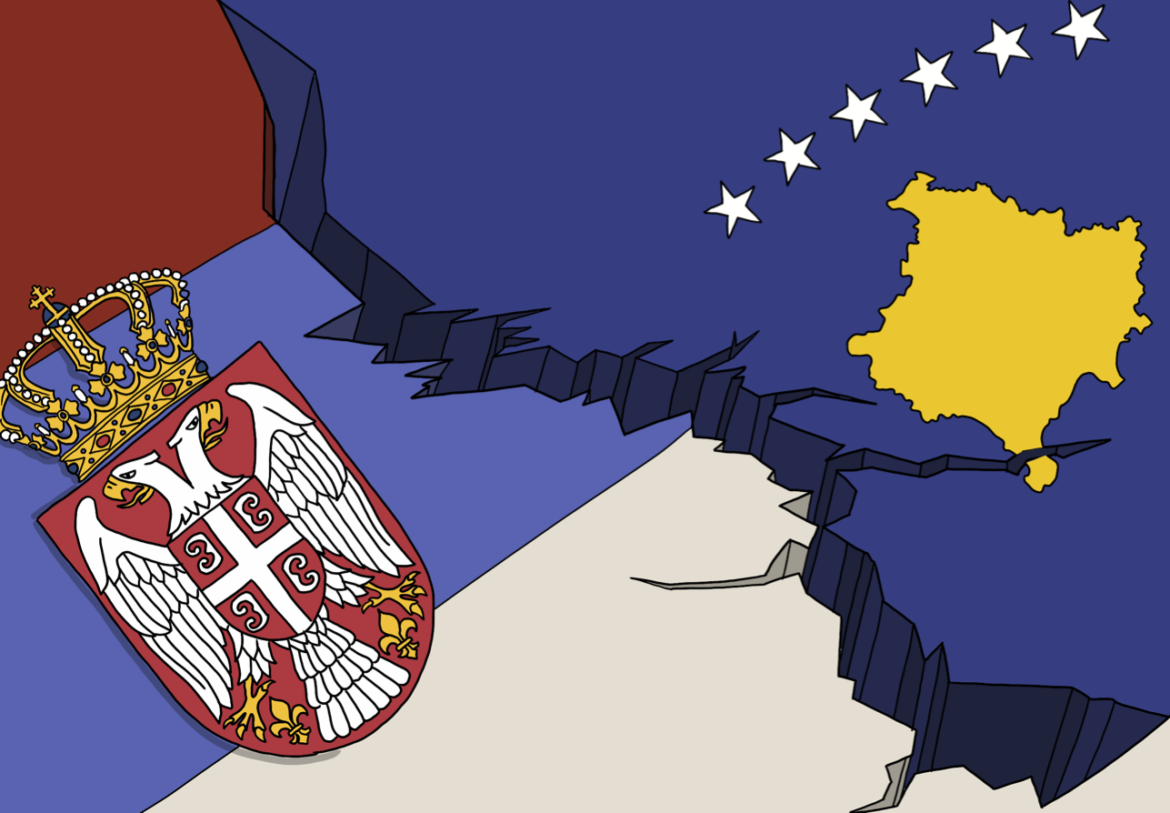

International eyes have turned to Kosovo once again, as echoes of the 1990s are threatening to re-ignite ethnic conflict and regional instability.

For the past 20 years, Europe has been fortunate to observe regional disputes outside its geographical borders. Since the end of the Second World War (WW2) and the end of the Cold War, relative peace and stability has bestowed a sense of collective action. Such collective action seeks to uphold values of democracy and political stability, increased treaty-building, and the expansion of countries that would join social ties under the European Union. The subsequent fall of the Berlin Wall in November of 1989 brought winds of change into much of Central and Eastern Europe, alerting leaders and citizens at-large that communism, lack of cohesion, the concentration of power to elites, and abuses of power would no longer go without significant resistance. However, Southeastern Europe fared differently, as ethno-nationalist movements prompted the dissolution of powers, prominently in the former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, which was made up of six individual states. These states include Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia (encompassing two autonomous provinces, Kosovo and Vojvodina), and Slovenia. After Yugoslavia’s President Josip Tito’s death in May of 1980, political and economic destabilization forced the wealthier states of Croatia and Slovenia to secede, leaving the four other members to seek similar actions in an attempt to provide their citizens with better living conditions. Conditions did not improve for all– Serbians, in particular, faced the most impactful conflict in Europe after the two World Wars in their southern province of Kosovo. This is due to the seventy-eight day bombing campaign by NATO bombers, thousands of casualties in Serbia, and controversial military targets by international forces that exacerbated the civilian impacts in Kosovo’s surrounding regions.

Recently, Kosovo has felt ethnic tensions at a high, with international eyes turned towards conflict onset by northern municipal elections held in April 2023. This marked a turning point for the region, threatening to reignite this complex history of Balkan instability.

In order to better understand the current situation in Kosovo as well as the implications that the latter is having on citizens living within these regions, it is necessary to take a look into the history of ethnic tensions and political unrest in Kosovo.

After Yugoslavia dismantled their centralized government in 1991 and 1992, political fallout was felt in Serbia’s provinces of Kosovo and Vojvodina. Both regions are multi-ethnic due to immigration and conflict dating back to the Habsburg Monarchy, Axis occupations during WW2, and post-war communism. In 1992, Kosovo had an estimated 83% Albanian majority and 10% Serbian minority, with the other 7% accounted for by refugees and immigrants. In Vojvodina, Serbians were a slight majority of the population (33.8%), followed by Hungarians (28.1%) and Germans (21.4%). While Vojvodina maintained a stable governance structure, Kosovo’s Albanian-predominant population had greater political influence over Serbians, which President Milošević in Serbia’s capital of Belgrade opposed. To counter this, Milošević’s government, composed of Serbian police, the former Yugoslav army, and Serbian paramilitary units, commenced a series of prosecutions against Albanian groups, eventually resulting in a devastating loss of 10,000 citizens under Operation Horseshoe. Albanians were forced from their burning homes and businesses, and were further implicated under NATO-led bombings of Operation Allied Forces, aimed at ceasing the ongoing conflicts.

Presently, Serbia does not recognize the independence of Kosovo, along with another 100 countries that refuse to hold diplomatic relations with the independent state. They propose that Kosovo has always been part of Serbia in an autonomous capacity rather than independent and that Kosovo is the “cradle of the nation” making the loss of control synonymous with losing the heart of Serbian identity and the ability to effectively hold onto nationality. This is significant as it demonstrates a commitment to maintaining what it means for Serbians to be “Serbian” in the eyes of their government.

On April 23rd, 2023, four municipalities in North Mitrovica, Zubin Potok, Zvecan, and Leposavic held elections for mayoral positions and assembly postings. Voter turnout was reportedly at a historically low level (3.47 percent), with a staggering 1,567 out of 45,000 eligible voters casting a ballot on this day across 19 polling stations. This can be explained by a voter boycott by the Serbian majority in the population, protesting Kosovo’s majority Lëvizja Vetëvendosje populist party (English: Self-Determination Movement) and Albanian nationalist movement. The party bases itself on building a state independent from Serbia, against “colonial thinking and aggressive Serb nationalism” and the freedom to self-rule within an autonomous, representative system of governance. The boycott was called for by the Srpska Lista party (English: Serbian List; the largest party representing Serbians in northern Kosovo) after withdrawing all candidates from running for elected positions due to their continued ethnic repression and lack of representation in governmental institutions. Namely, their conditions for cooperating with Albanian organizations necessitated the development of an official Association of Serbin Majority, the withdrawal of Kosovo’s Special Forces (KFOR) from the north, and the right to register a vehicle under Serbia rather than Kosovo, all of which have not been achieved to date. Across the country, most of Kosovo’s Serbs that would have been represented by the Srpska Lista (at least, in their region) account for 96 percent of the population in the north while collectively amounting to a mere 1.5 percent of the population. The rest of the ethnic makeup in Kosovo is a melting pot of 95 percent Albanians, 2 percent Bosnians, and the other 4 percent accounted for by various ethnicities. Out of four positions up for election, all spots were won by Albanians, only furthering tensions and decreasing the likelihood of any positive Serbian unification.

The European Union has condemned the decision of Serbian boycotts across the country, uniting countries such as France, Germany, the United States, Italy, and the United Kingdom in stating that they “deeply regret” this demonstration of refusal to participate in their democratic system and that it would not result in a “long-term political solution for these municipalities”. Further, the international community has been quick to note that this is indicative of gradual democratic backsliding, where Serbians will undergo a process of less political participation, increased repression, and arbitrary demonstrations of power on behalf of Kosovo’s government, which presently occupy the northern regions alongside NATO forces.

After the elections in April, May 2023 witnessed Kosovo’s Albanian-maintained government sparking outrage once again for these Serbian-majority regions. In Zvečan, dozens of citizens have been injured in physical combat against KFOR, resulting in the deployment of an additional 700 troops in a NATO-led task force onto the ground. Instead of a waving Serbian flag, the distinctive gold outline of Kosovo now exists with six surrounding white stars against a blue backdrop flying in northern municipal buildings, further alienating the Serbian minority from spaces that used to be a safe haven. Additionally, Serbian forces have rallied along the border shared with Kosovo after Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić notified his army about NATO forces in the north. This opposition to NATO forces and KFOR comes after the 1999 United Nations Security Council ruling, which prohibits Serbian fighters from entering Kosovo.

Humanitarian impacts on citizens are shockingly similar to the conflicts of 1998-99, which left Kosovo’s Serbian community frightened of both their government and external forces such as NATO, the UN, and KFOR, which have deemed themselves peacekeepers. This echoes what the international community should have learnt during the NATO-led airstrikes and interventions in Kosovo from March to June of 1999: to intervene using a cohesive strategy and long-term deployment of troops on the ground. While NATO forces were ready to bomb Kosovo, many citizens were negatively impacted, with an estimated casualty of 500-2,500 civilians retrospective of deliberate targeting. Operation Allied Force in Kosovo undercut international humanitarian standards outlined in the Geneva Conventions, particularly under articles 13 and 32, which necessitate actors to actively facilitate the protection of civilians from discrimination due to race and other factors of identity. Greater hostility between Serbians and Albanians resulted from NATO’s intervention, instilling a years-long conflict still felt in political unrest, repression, and fear of persecution for the Serbian minority.

What is now the repression of Serbians in Kosovo reverses the anti-Albanian rhetoric demonstrated within the country throughout much of the 1990s. Albanians who Serbian and former Yugolslavian-led groups prosecuted are now pushing back in retaliation for the crimes committed against their majority. While Europe is not unfamiliar with conflict in the Western Balkan regions, this ongoing ethnic conflict in Kosovo sheds light on the increasing persecution of ethnic minorities in regions with longstanding political tensions.

The United Nations Special Rapporteur Fernand de Varennes stated in March of 2023 that the Donetsk region of Ukraine has also felt significant targeted attacks against their population by Russian invaders, a geographical region that is home to ethnic Greeks, Ukrainians, Jews, and Armenians. Further, he has urged all parties involved to ensure that protection and humanitarian assistance are provided to civilians caught in the crossfire, regardless of ethnicity. The same should be said for ongoing conflict post “humanitarian interventions” in Kosovo. Both events simultaneously occurring in Europe bring eyes to international organizations again and pressure those becoming involved to re-examine their positioning and actions. The focus on preventative measures to ease conflicts should be prioritized, all while looking back in time to identify problems that cannot be repeated.

Edited by: Sabrina Nelson

Olivia Bornyi joined the Catalyst team in January 2023, bringing with her a fresh and critical analysis of political relations and development studies. She is entering her fourth year of Political Science and International Development Studies at McGill University, and just completed a semester abroad at Sciences Po in Paris, France! Olivia’s research interests include security studies, social discourses on political relations, humanitarian diplomacy, and comparative studies of development. Outside of academics, Olivia enjoys planning future travels, knitting, and discovering new cafés in Montréal.