Geerts Wilder, leader of the PVV or Freedom Party, won 37 seats out of 150 in the Dutch elections on November 22 of this year. Mr. Wilders is a political figure characterized by his radical views on the subject of the European Union and immigration. If he is able to form a coalition, he is likely to become the country’s new prime minister. This event exemplifies a broader shift in Europe towards right wing parties, with countries like Italy, Germany, Poland, Finland, and France moving towards right-wing rule as the respective parties of these camps have either gained support or extended their rule in national elections. Could this trend alter the face of European politics?

Wilder’s political journey began in 1998 as a member of the Dutch House of Representatives. He formed the PVV in 2006 and has now expressed his intention to become Prime Minister of the country. His party intends to tackle a variety of issues in its election program, some of which include a push for a more “more restrictive immigration policy,” “a binding referendum on Nexit,” as well as supporting “more oil and gas extraction from the North Sea and keeping coal and gas power stations open.” Whether Wilder will be able to apply his ideas depends partly on whether he will be able to form a coalition government. However, a coalition will likely also demand compromise and could moderate his views, actions which may not be amenable to the preferences of Wilder himself.

These results demonstrate a radical shift from the outgoing prime minister Mark Rutte who has been the Netherlands’ longest-serving prime minister, boasting a tenure of 13 years. Recent elections show that the Netherlands is shifting away from its image of being one of “the most socially liberal countries” and towards more conservative, right wing values. Additionally, fragmentation and discontent is not novel in the nation, rather it has been growing gradually over time with subjects like the question of immigration policy accentuating these divisions. Division is also exemplified in the political landscape, evident with the 20 different parties in the House of Representatives alone, as well as diverging parties in society depicted within a report from last year by the Netherlands Institute for Social Research; revealing that 60 percent of Dutch people are unhappy with the politics of the country.

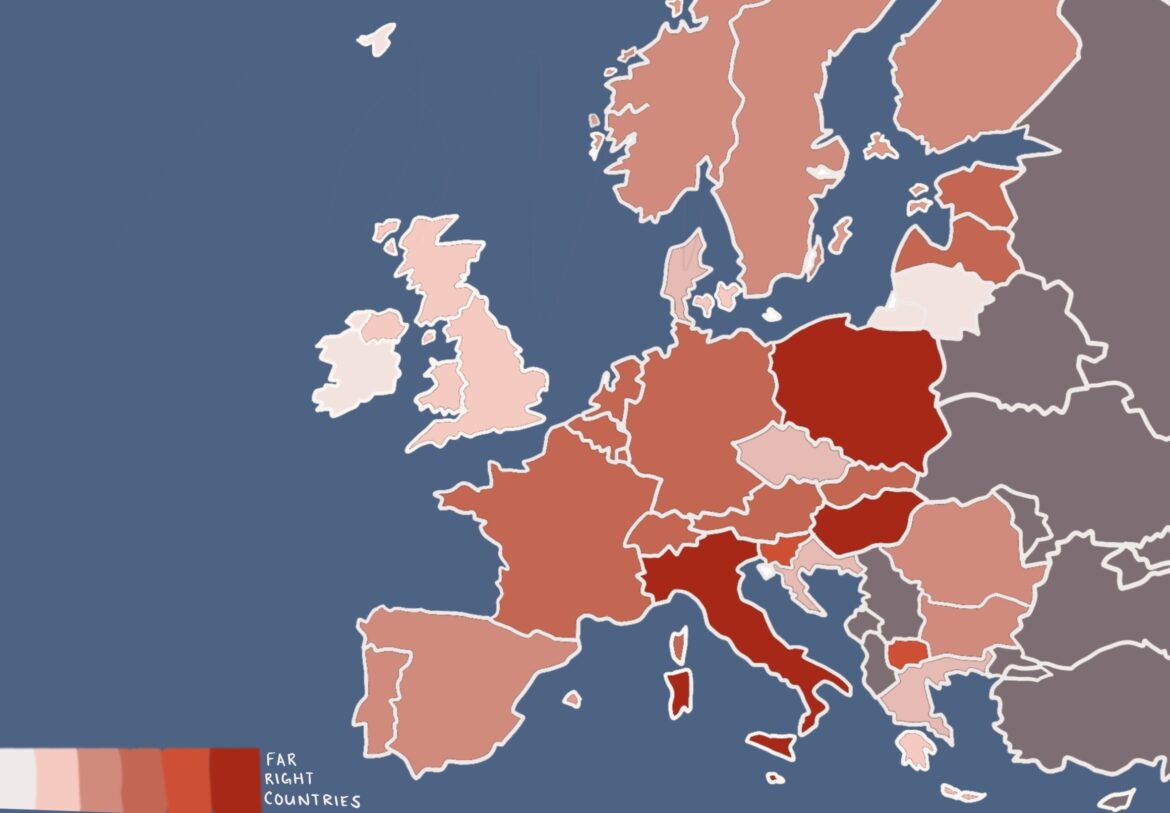

Wilder is not the first right-wing candidate to win elections in Europe. Indeed, there has been a noticeable rise in right-wing and far-right politics across European countries as of late. For instance, in Italy, Giorgia Meloni, head of the right-wing coalition made up of Brothers of Italy, Northern League, and Forza Italy won elections in September 2022. In France, although current President Emmanuel Macron won the 2017 elections against right-wing party Front National represented by Marine le Pen, the party posed the most significant opposition. The candidate received the most support she has ever had, gaining 41.45 percent of votes in the presidential elections. In Germany, the Alternative for Germany party (AfD) shifted from solely a regional party to becoming a significant national party: in 2017 the party gained 12.6 percent of the vote and entered the federal parliament. In Hungary, Victor Orban has ruled the country since 2010 as head of the conservative party Fidesz. In Finland, the far-right True Finns party gained power as part of a coalition for two years, holding 17.7 percent of votes in 2015. Additionally, Britain has shown signs of similar right-wing voting tendencies, marked by the conservative-lead decision to exit the EU back in 2016. In terms of demographic, this shift has a significant impact on the European Union as four of the five most populous countries contain right wing parties either in government or have right wing parties bringing in above 20% of votes according to polling data.

It is inevitable to turn to asking what explains this trend. Causal factors vary from country to country. However, growing political dissatisfaction is plausibly correlated. Such dissatisfaction is seen to be coming out of rising inflation in the energy sector, stemming from the Ukraine war and sanctions against Russian oil, as well as political division on the question of migration alongside increasing immigration rates. In the Netherlands, the latter is exemplified by a report from Statistics Netherlands which revealed that immigration rates have doubled in 2022 in comparison to the previous year, amounting to a total of 223,000 people. Similarly, asylum applications in the Netherlands reached over 46,000, and estimations project this number to rise to 70,000 this year. Both subjects are at the forefront of the recently elected conservative party’s political agenda. Politicians have also increased polarization on these subjects by associating immigration issues with the housing crisis to rally support.

Furthermore, right wing parties have expressed radical ideas to reform their country and Europe more largely through institutional measures. The impact of this upon the rise of these relevant parties although, is still strongly debated. On the one hand, media outlets like the Guardian have downplayed the influence of right-wing parties. For instance, they have depicted Italy’s prime minister as being more moderate compared to at the beginning of her mandate. Other indicators which may point to moderate politics is that the rise of right-wing politics has not been uniform. Some countries are more radical than others. Some countries have even experienced backsliding, such as in Spain where the conservative party, Popular Party, lost support in the July elections, and in Poland where the conservative party, Law and Justice, did not win a majority of seats in the October 15 elections. On the other hand, other media outlets like the Washington Post argue that far-right parties are capable of bringing change by influencing policies both domestically and in the EU at large. The article refers to the way far-right parties have been able to slow parts of the green transition in Sweden, Britain, and Germany.

What the future holds for right-wing politics in Europe is yet to be seen; nonetheless, if support for right-wing parties continues to grow, this shift could constitute a defining moment for the politics of the European Union and those of its member states.

Edited by Justine Delangle

Victoire Thierry is entering her third year at McGill university studying International Development and Political Science. She is a first-time writer and her interest include sustainability, migration and international relations.