Joyland, directed by Saim Sadiq, has become one of Pakistan’s most controversial films. The movie is about Haider, a stay-at-home-husband, who is forced to find a job due to pressure from his father and ends up working as a backup dancer for a transgender starlet at an erotic dance theatre, where they form a relationship. He lives in a joint family system with his father, his brother’s family, and his wife. In this house, the viewers observe sexuality and desire between the relationships and dynamics of all the characters, with the backdrop of the middle-class typical Pakistani lifestyle.

The movie has screened at important film festivals since its debut in November 2022, including Toronto and the BFI London Film Festival, where it won a special mention. It was also awarded the Cannes Queer Palm and Un Certain Regard Jury Awards. It has been shortlisted for the Oscars’ Best International Feature Film category, although fell short of the nomination, but has been nominated for Independent Spirit Awards’ Best International Cinema.

Joyland has achieved many firsts for Pakistan’s film industry and created room for contentious discourse on Pakistan’s core issues with gender and sexuality. Despite this, the government banned the movie nationwide. The questions are: Why is such a powerful film banned in a country facing its reality? What reality is it shying away from? The Ministry of Information and Broadcasting commented that “written complaints were received that the film contains highly objectionable material which do not conform with the social values and moral standards of our society and is clearly repugnant to the norms of ‘decency and morality’ as laid down in Section 9 of the Motion Picture Ordinance, 1979.” The ban came after right-wing Islamic groups complained that it promoted homosexuality. While it has since been rescinded, the ban has remained in place for the country’s largest province of Punjab, which is also the film’s setting.

Spearheading the campaign against Joyland is right-wing Jamaat-e-Islami senator Mushtaq Ahmad Khan. “In front of the pressure of the foreign, secular lobby, the government collapsed. It is a misfortune for Pakistan that a movie in LGBTQ category, nominated for Oscar is granted permission for release,” he tweeted, expressing his disappointment with the lift of the ban. I am fighting against LGBT @SenatePakistan, Judiciary, Media while staying within the circle of law and constitution,” he also commented in his twitter rage that “A Pakistani film getting an award in the LGBTQ category is like a slap on the face of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan.” The politician also claimed that Joyland is against the institution of marriage.

It can be argued that one transphobic senator is not a threat to the entirety of Pakistan and its efforts toward becoming a safer country for everyone. Indeed, the problem is much bigger, and it is difficult to decipher whether the issue is that the movie is against religion or whether the topic of sexuality is a cultural taboo. Director Saim Sadiq commented that religion is merely an excuse for the ban, rather, “It’s mostly people trying to avoid discomfort that stems from the idea that people have sex.” While this may be one explanation, it is relevant to discuss how, in the precarious State of Pakistan—where religion is the one identity that connects its people and purpose— how manipulating religion to disseminate dangerous rhetoric plays a role in the sociopolitical fragmentation of society, but particularly in the regular lives of the transgender community.

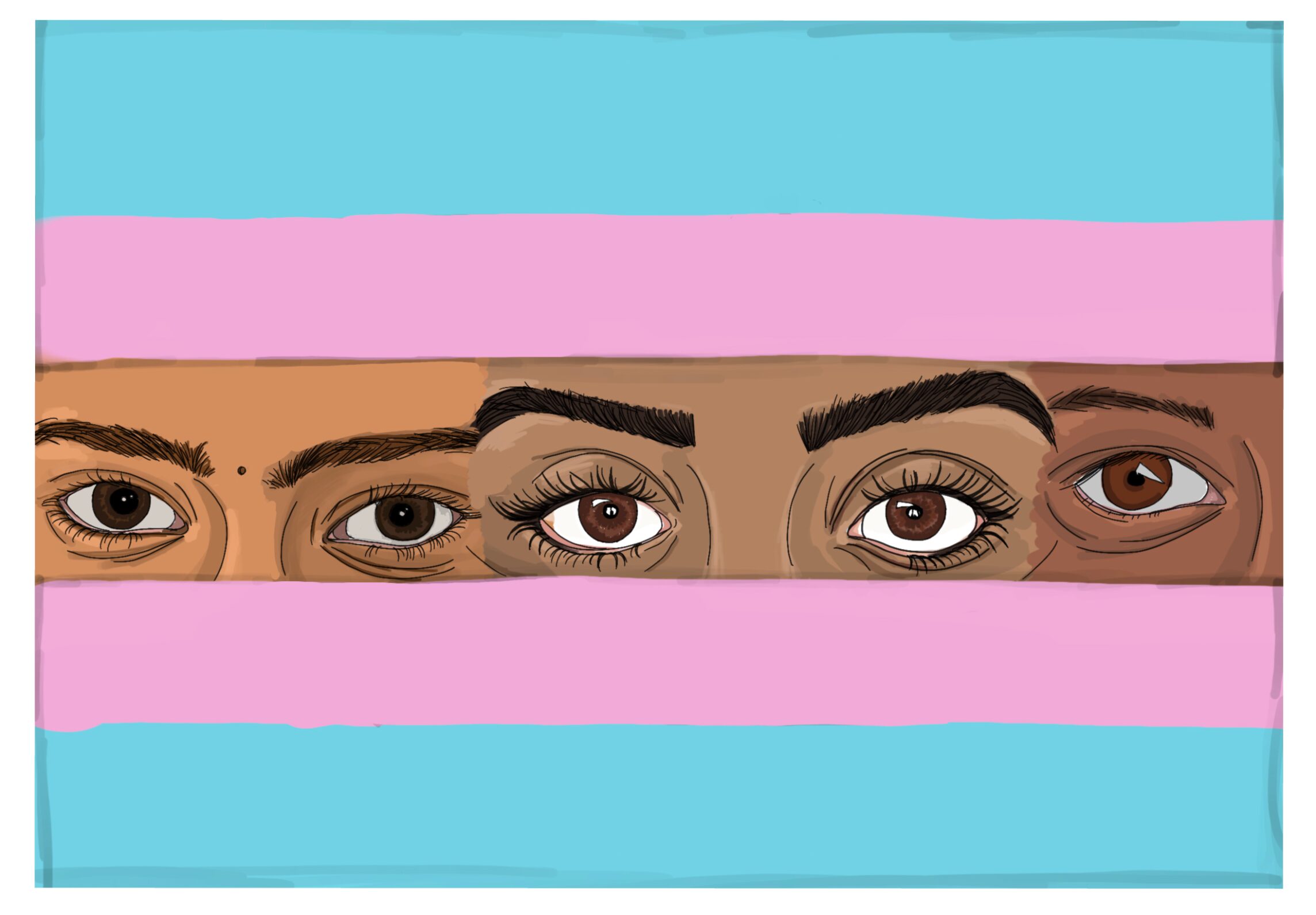

It is true that politicians in the country’s entire history have used religion to suit their political agendas, notably during Zia-ul-Haq’s authoritarian regime and his Islamization of the country. The depiction of a trans woman in the movie has been a key point of debate. Transgender persons, especially transgender women, are shunned in Pakistani society and often disowned by their families. This group of people, known as Khwajasira or the “third gender”, has been part of Pakistan and South Asia for thousands of years. 147 years ago, the British empire classified Khwajasiras as a “criminal tribe”, which many argue was the beginning of transphobic sentiment and which changed the trajectory of the transgender community in the subcontinent at large. This community is nowadays a visible, marginalized group.

Most transgender women in Pakistan live in communities for safety and survival. They face immense human rights violations and social ostracization. Due to the pervasive stigma and discrimination, such as lack of education—42% of the trans community is illiterate—employment equity, and opportunity, many transgender women work in extremely dangerous conditions and are forced towards professions such as sex work, sex trade, and begging. Consequently, the community faces extreme psychological trauma and mental distress. To cope with these realities, many survivors abuse drugs and substances.

Legally, transgender people were recognized as a “third gender” by a Supreme Court of Pakistan ruling in 2012. Then on May 8, 2018, Pakistan enacted the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act, which recognises the rights of transgender citizens. The Act is to “provide for protection, relief and rehabilitation of rights of the transgender persons and their welfare and for matters connected therewith and incidental thereto.” It grants transgender people rights to identity cards where they can choose their gender. Before this, the National Database & Registration Authority could not issue Computerised National Identity Card (CNICs), which meant that the trans community had no access to state services or even legal documentation required for opening bank accounts, obtaining a passport, purchasing vehicles and land.

The Act prohibits harassment, provides inheritance rights, and solidifies human rights as trans rights. In essence, this was a game changer for the Pakistani trans community, and even for Asia as it became the first country in the continent to recognize a self-identified gender legally. In reality, however, the implementation has been inadequate.

Since September 2021, 18 transgender people have reportedly been killed in Pakistan, which is likely an underestimation of the unreported violence because, in 2022, as many as 70 transgender people have been murdered in the KP province alone. This past November, Pakistan held its first Moorat March, a trans pride march in Sindh, which expectedly did not receive much media attention. However, it has been a step towards progress.

At the crossroads of religion, politics, and tradition, the trans community faces the blunt force of exclusion. Zarish Khanzadi, a trans woman, remarked “there was momentum for acceptance of transgenders, but religious parties made this Act as part of their political agenda just to gain seats, undermining the respect of our gender identity.” Indeed, this is where much of the frustration lies. It is natural to ask right-wing, self-proclaimed, so-called maulvis about what they represent: narrow-minded, patriarchal, and outright false interpretations of Islam. When will this relatively small but powerful group of individuals recognize the harm they are disseminating in a country deprived of assurance? Their twisted ideologies and manipulation of religion are hurting the foundations of the country, who it was built for, and what it was meant to stand for. Regarding religion and gender violence, it is imperative to open discussions on what Madrassahs in low-income rural areas do to children behind closed doors. There have been increasing reports of all types of abuse in Madrassahs, and an increasing role of sexual abuse of street-children. Moreover, there is a rapidly increasing rate concerning the rape of women.

It is these issues of what it means to be a woman, cis or trans, in an Islamic country that these leaders are failing to address. Instead, ideas that invalidate gender, sexuality, and all types of people cost the country social development. Using religion as an excuse against trans rights has no validity until the institution of religion is upheld and implemented properly and with dignity in Pakistan. Such mentalities need to face the realities of what sexuality and gender truly look like in Pakistan.

Although Joyland is still banned in Punjab and censored in other parts of the country, it is also a step towards progress. The movie is a masterpiece showcasing regular people’s complexities, nuances, and desires. It has highlighted and humanized a transgender woman instead of mocking and using her as a comedic relief character, as is common in Pakistani media. It has highlighted that harmful patriarchal values hurt men, women, children—everyone. The movie has created a platform for discussion on previously taboo topics. Although religious debate sparks controversy, perhaps it is time to sort out these conflicts instead of shutting them down.

Edited by Sarah St-Pierre