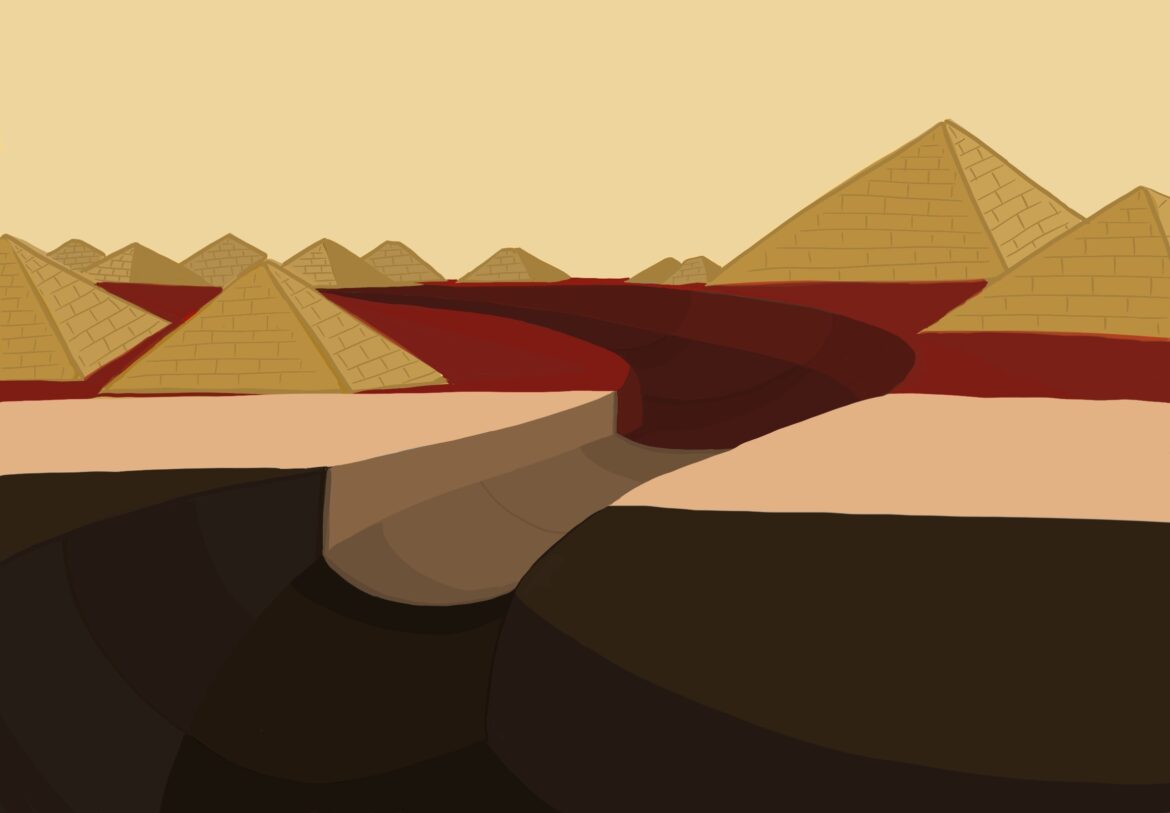

Water scarcity is a force to be reckoned with. It directly impacts agriculture, access to clean drinking water, and energy production. This climate phenomenon also exacerbates numerous other key issues, including health, infrastructure, social inequalities, and conflict. The latter is particularly heightened in the case of Egypt and Ethiopia, two countries long embroiled in political disputes over the Nile River. This conflict has recently escalated due to Ethiopia’s dam project, which Egypt views as a direct threat to its already precarious water security. These tensions raise an important question: as climate change intensifies and political tensions escalate, could water scarcity trigger the next major war?

Egypt’s dependence on the Nile River as a primary source of water and energy is huge. Due to the significant amounts of silt carried by the river, the surrounding soil is extremely nutrient-rich and ideal for agricultural production. Thus, Egypt has long depended on the Nile Delta region for its crop harvests and the growth of papyrus, a key commodity for the Egyptian economy. The Nile also supplies hydroelectricity to Egypt’s population via the Aswan dam. As of this year, nearly 95% of Egyptians live within only a few miles of the Nile, highlighting the Nile’s critical role in multiple sectors of Egyptian life.

Currently, around 90% of Egypt’s current water supply comes from the Nile. As of 2021, the country’s annual share of the river’s supply stands at about 55 billion cubic meters. However, Egypt’s rapidly growing population requires at least 90 billion cubic meters annually, leaving the country in a severe water deficit. This deficit leaves Egypt vulnerable to changes in climate, political instability, and shifts in the river’s flow.

Flowing through 11 countries, the Nile creates a complex web of interlinked environmental and political interests. Thus, what happens upstream inevitably affects downstream nations like Egypt. Enter Ethiopia. With construction starting in 2011 and now nearly finished, the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) is situated along the Blue Nile tributary in Northwestern Ethiopia. The purpose of the dam is multifaceted: it aims to provide hydroelectricity to up to 60% of Ethiopia’s population, boost economic development, supply irrigation to agriculture, and foster national progress.

However, Egypt sits unsettled. Having already experienced decreased river flow due to the effects of climate change, the establishment of the GERD threatens to further decrease the amount of water flowing downstream, impacting the country’s own water supply. The dam’s reservoir began filling in 2020, and a recent study suggests that should this continue, “Egypt’s Nile water allocation might be reduced by 35.47 ± 2.29 % […], which could translate into an agricultural land loss of 33.14 ± 1.81 % each year.” As a result, the nation’s fears are certainly not unfounded.

The political tensions surrounding the Nile River are not new, stretching back over the last century. The first agreement which sought to address the issue was between Egypt and Great Britain in 1929. It granted Egypt a fixed amount of water per year, as well as the power to veto any upstream construction of development projects in or closely surrounding the Nile. More importantly, this agreement was not signed by any of those upstream countries. In 1959, Egypt and Sudan signed an agreement reinforcing the 1929 provisions, but once again, upstream nations were excluded.

As population growth has surged in upstream nations, their voices have grown louder in challenging these historical agreements. While the 1959 agreement remains technically valid, upstream nations argue that they were never signatories and therefore are not bound by its terms.

In 2010, four upstream nations signed the Cooperative Framework Agreement(CFA), which sought to establish equitable water distribution among the Nile Basin countries. Egypt and Sudan strongly opposed the CFA, rejecting it on the grounds that they had “acquired rights” to the river, and that the CFA infringed on those rights. In 2015, a newer agreement was reached acknowledging the need to move beyond the colonial-era treaties, but it offered little in the way of concrete solutions. It was more of a pledge to continue negotiations than a resolution. Egyptian concerns over the GERD remain high, and construction continues.

To date, water has not directly caused an armed conflict. However, as seen with the recent worsening of climate change, there is a first time for everything. Abiy Ahmed, the Prime Minister of Ethiopia, stated in 2019, “If there is a need to go to war, we could get millions readied.” Badr Abdelatty, Egypt’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, has also emphasized: “We will defend our interests within the framework of international law,” and that “If our security and interests are threatened, we will not hesitate to act.” Furthermore, recent negotiations regarding the filling of the GERD have stalled.

Climate change is ushering in a new age of potential conflict. The serious possibility of resource depletion brings about a looming threat of war between Egypt and Ethiopia. However, both countries are aware that war is detrimental to all. Prime Minister Ahmed has also acknowledged that war would “not in the best interest of all of us.” Officials remain hopeful that an agreement satisfying both parties will be reached. As this era of environmental shifts continues, the need for cooperation is crucial to prevent the breakout of a full-scale resource war.

Edited by Isaac Yong