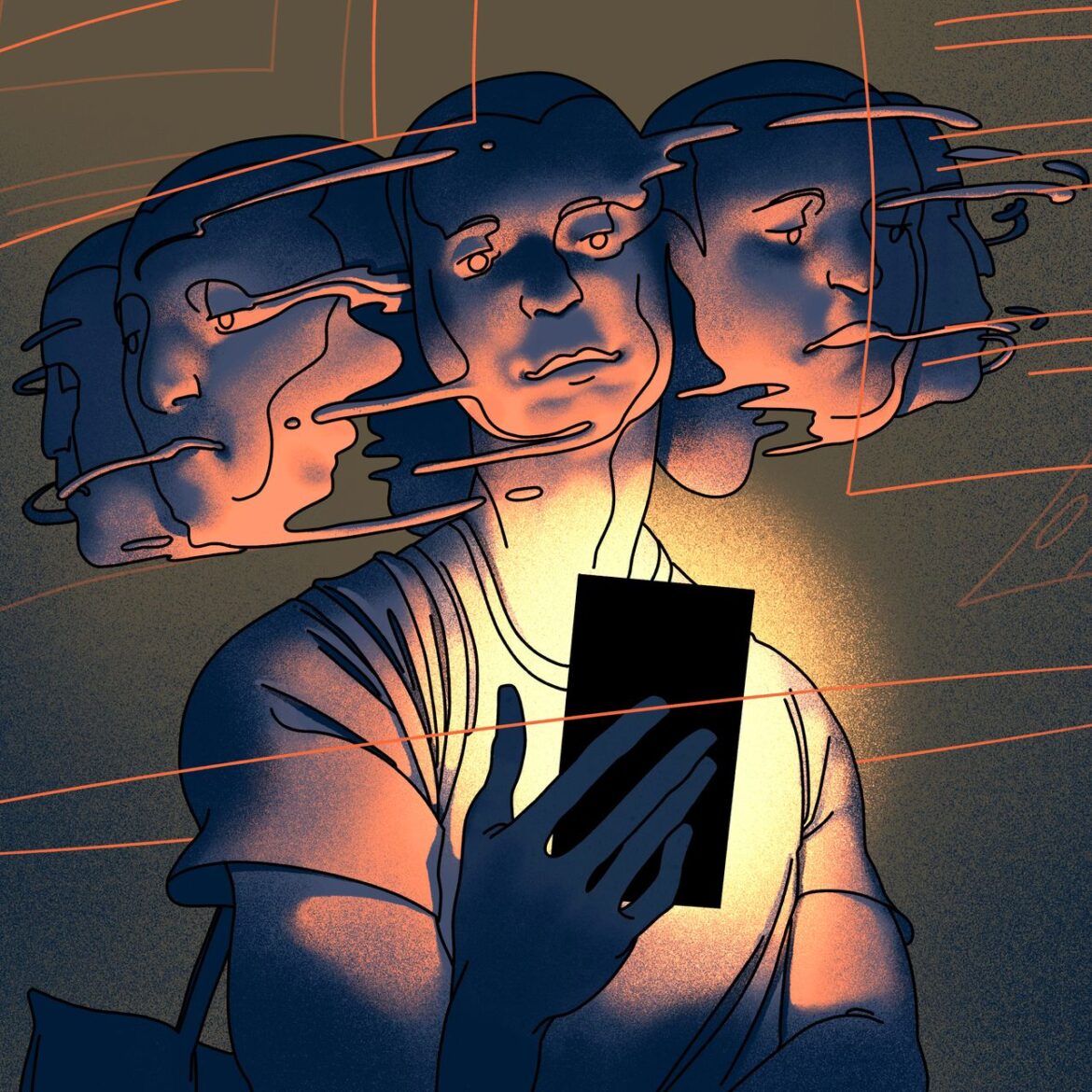

In the intricate realm of global geopolitics, the narrative of empathy within Western media reveals profound patterns of selectivity, spotlighting certain oppressed groups while relegating others to obscurity. This article delves into the phenomenon of the ‘Perfect Victim’ myth, revealing how Western media’s portrayal of empathy is both continuously selective and deceptive.

In navigating the recent terrain of global geo-politics, one might feel the palpable tension that exists between those in the Global North, in specific, their media outlets, and their subsequent ability to engage in the plight of persecuted communities. This approach has been marked by a tendency to address raw human suffering, philosophically, as if wholly detached from the lived realities of those subjected. Within the myriad of detrimental consequences being born from such a lens, one is frighteningly discernible: a myth, deeply ingrained in Western consciousness, that has presupposed a narrow template on non-Western groups’ victimhood that fails to capture the ways individuals and communities navigate their paradigms of power and privilege.

Central to this myth, known as “the perfect victim” fallacy, is that it sets unrealistic expectations for oppressed individuals around the world to adhere to Western standards of rationality and non-violence in their resistance to be “comfortably” digested. Of course, it is important to note that this notion of “non-violence” is not uniformly applied; and past resistance movements exhibited by those in Ukraine or Bosnia are not only permitted by Western media outlets but celebrated–hailed as legitimate sufferers in a quest for justice. This calls into question whether this imposed moral code is truly about adherence to non-belligerence by the suppressed group, or rather a dictation of who is being judged by this standard and who is afforded to be exempt.

Victims of oppressive systems, and predominantly those of the Global South, are relentlessly compelled and continuously called upon to conform to these predetermined categories; wherein they are either perceived as deserving of compassion or relegated to the margins of societal empathy. This nonsensical dichotomy dictates that individuals must exhibit traits of passivity, helplessness, and acquiescence to their subjugated position to warrant the concern and support of Western society–whether it be an ephemeral personal view of one citizen or the sending of overwhelming aid by global powerhouses. However, naturally, colonised people will develop deeply complex reactions to their suffering, outside of the categorial “good” or “bad”. Those who dare to resist or assert their agency have the unfortunate fate of being deemed unworthy of empathy, their actions portrayed as irrational, confrontational, or even deserving of further oppression. It goes unsaid to say this expectation overlooks the profound psychological toll of systemic violence and dehumanisation; and disregards the visceral reactions stemming from generations of trauma and dispossession.

What seems to be forgotten within this discourse is that persecuted peoples throughout history have rarely conformed to the passive victim narrative imposed upon them by the dominant group. A poignant example of this can be found in the historical milieu of apartheid in South Africa, where resistance efforts against the oppressive regime were often met with denigrations and characterizations intended to undermine the legitimacy of their voices. Those who opposed apartheid policies were frequently vilified by the ruling authorities. Similarly, in contemporary contexts, individuals and groups who challenge the status quo and are ultimately coerced to assert their rights after decades of forced apathy are met with accusations of incitement and extremism. These labels, wielded by entrenched power structures and vested interests, cast them as threats to societal stability and security. However, we must pay attention to the deliberate characterization of resistance movements as inherently violent or destabilising, as a manipulation tactic by authorities to justify the implementation of draconian measures aimed at maintaining the existing power dynamics by any means necessary. By framing dissenting voices as threats to public safety or national security, oppressive regimes seek to justify the curtailment of civil liberties and the continued suppression of political opposition.

Indeed, to unpack this contrast further, it is interesting to note that in Ukrainian resistance to Russian aggression, a discernible disparity emerges in the treatment and portrayal of acts of resistance compared to the latter conflicts. Instead, Ukrainian efforts to defend their sovereignty against external encroachment are depicted through a lens of heroism and unbridled national defence. The media frames an innate valour and fortitude exhibited by Ukrainian soldiers and civilians amidst their suffering. Rather than facing countless interrogations regarding the legitimacy of their pain or asking them to condemn acts of resistance by people who are unbeknownst to them, Ukrainian resistance is positioned within the framework of a just response to an existential menace. Ordinary Ukrainian citizens innocently ensnared within the vortex of conflict are granted universal empathy—a “luxury” few are afforded today.

While one can recognize the nuance between more recent examples in Palestine and the war in Ukraine, it is important to reflect on why this media framing persists for those under an “orientalist trope” and whether it’s simply a question of differentiated levels of moral clarity, or perhaps, something more sinister: an adverse tendency within Western discourse to exoticize and otherize non-Western societies, often portraying them as inherently chaotic, backward, or prone to violence, even in their victimhood. Here is where we can best recognize the myth of the “perfect victim” as a tool of social control, dictating who is deemed worthy of empathy and support based on arbitrary criteria of acceptability and compliance made true by existing orders of power control around the globe.

Altogether, the classification of victims into simplistic categories of “good” or “bad,” or even the romanticization of some as “heroes,” serves to trivialize the realities of suffering experienced by individuals and communities worldwide. Lived injustice that we have the privilege of being a mere witness to does not deserve a clear-cut dictation, so passive observers can be offered a false sense of comfort. This haste towards moral classification fosters detachment in a world already plagued by a lack of nuanced empathy and understanding. Let us resist the temptation to reduce injustice to simplistic narratives and instead commit ourselves to the pursuit of genuine understanding. In doing so, we can move beyond passive witnessing and become truly active agents of compassion and justice in a world that sorely needs it.

Edited By Ailish McGiffin

Katerina Ntregkas is in her second year at McGill University, currently pursuing a degree in International Development Studies with a minor in Communication Studies. As this year’s Staff Writer for Catalyst, Katerina is determined in analyzing the discourse between the intersection of media and developing world politics.