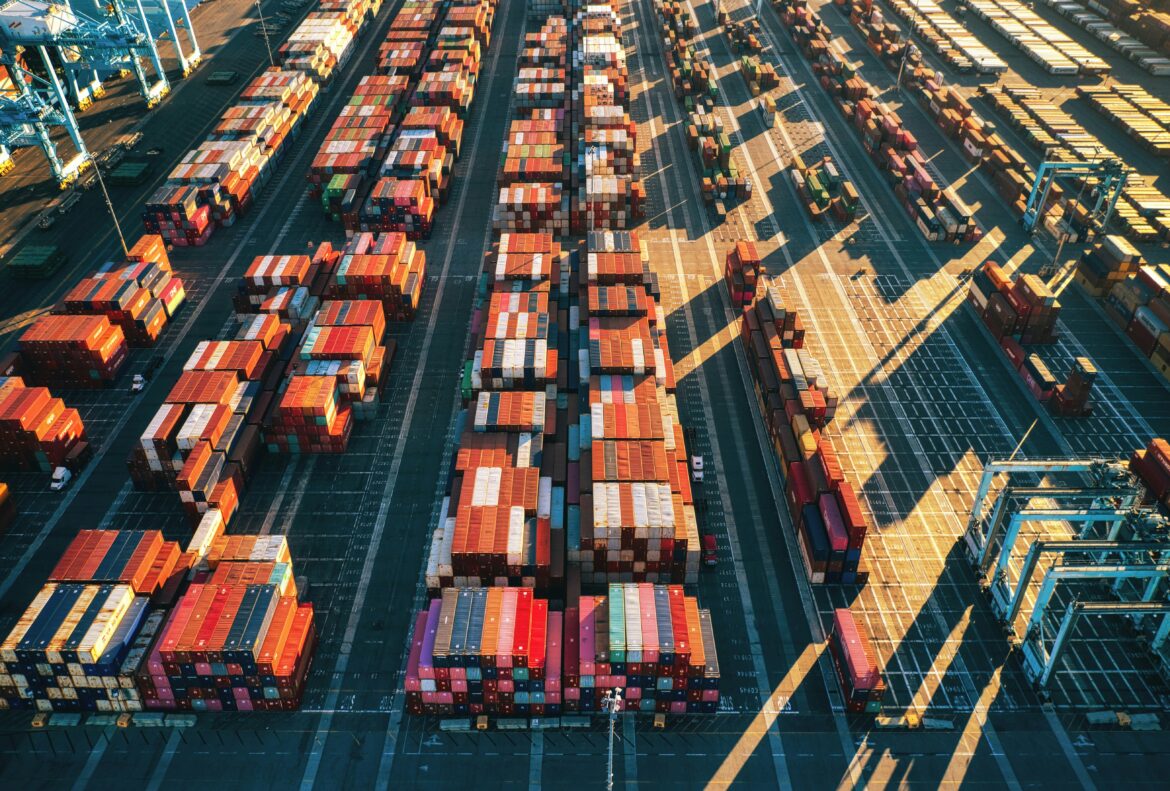

Shipping plays a pivotal role in global trade, handling approximately 80% of the world’s goods, making it essential for the functioning of the American economy. Disruptions can send shockwaves through supply chains, affecting prices and businesses worldwide. On October 1st, the International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA) initiated a strike, demanding higher wages for their members. Two days later, the strike was suspended till January, but the short-lived action revealed deeper tensions in the industry.

The American election landscape has been highly polarised and unusually dynamic. To name a few of the unusual events this election season, two assassination attempts on former President Trump and President Biden’s unexpected dropping out of the race to be replaced by Vice President Kamala Harris. These moments of political uncertainty are relevant to Unions as they are a critical constituency, and responses to strikes can sway this voting bloc. Both the Democratic and Republican parties are vying for the support of the working class, resolving labour disputes like this one politically sensitive. The Biden administration, seeking to court middle-class votes, encouraged the Maritime Alliance to present a more attractive contract offer. The administration likely had an additional goal of averting long-term disruptions during this precarious election season, which could alienate key voter bases reliant on uninterrupted supply chains.

Extended strikes in the shipping industry could have catastrophic consequences, particularly in this political climate. Amid public pressure, the Maritime Alliance put forward a contract offering a 62% wage increase over the life of a six-year deal. While this addresses aspects of the ILA’s concerns, the debate regarding the role of automation in shipping continues. This tentative agreement will be negotiated, and if an agreement is not reached, the strike may resume starting in January.

The introduction of automation has swept across various industries, including shipping. It involves the process of mechanizing tasks usually carried out by humans, for example, operating cranes and machines to organize shipping containers, navigating vessels, and optimizing logistics through real-time data collection and analysis. While automation can lead to increased productivity and cost savings, often translating into lower prices for consumers, it comes at the cost of jobs. This trade-off between progress and job preservation is at the heart of the labour movement’s resistance to automation. Industries like shipping are seeing a seismic shift as machines replace human labour in many roles, including cargo handling, vessel navigation, and inventory management.

The tension surrounding automation is best understood through the concept of structural unemployment. Structural unemployment occurs when there’s a mismatch between workers’ skills and the skills needed in the modern economy. As technology advances, certain jobs become obsolete, and workers who perform those tasks may struggle to find new roles unless they acquire new skills. This is unlike cyclical unemployment, which is tied to economic fluctuations; structural unemployment persists even in economic growth because the changes in industry demand are permanent. As automation accelerates, this type of unemployment becomes a long-term concern for industries like shipping. Harold Daggett, ILA union leader, said, “Timeout, this world is going too fast for us, machines got to stop,” and, “Who is going to support their families, machines? Machines don’t have families“. Unemployment often has significant social costs affecting families, mental health, and community stability.

The port of Rotterdam offers a glimpse into the future. In January 2016, it experienced its first strike in 13 years as workers protested against rising automation. Rotterdam is one of the world’s most automated and innovative ports today. It aims to host self-driving ships and containers communicating their contents, demonstrating how automation can revolutionize the shipping industry. While this increases efficiency and reduces costs, benefiting consumers and businesses alike, it also underscores the challenge of adapting the workforce to a rapidly changing technological landscape.

The argument for technological advancement has always suggested that while jobs will be lost in the short run, new jobs will be created in the long run. However, this transition can be painful for those displaced by automation, and it often takes time for workers to retrain and re-enter the workforce. An article by McKinsey suggested that future workers will see a change in their qualifications and required soft skills, focusing on managing people, applying expertise, and communicating with others. In the meantime, the impact on livelihoods can be profound, especially for those who cannot easily transition to new roles.

Ultimately, the strike by the ILA highlights broader issues at the intersection of labour, politics, and technology. As the shipping industry grapples with demands for higher wages and the encroachment of automation, resolving these tensions will affect not only the workers but also consumers, businesses, and the broader economy.

Edited by Olivia Moore

Anvita Dattatreya is in her third year at McGill University, currently pursuing a B.A. Double Majoring in Economics and International Development Studies. As a staff writer in Catalyst she hopes to write articles on topics including socio-economic and political issues in South-East Asia.