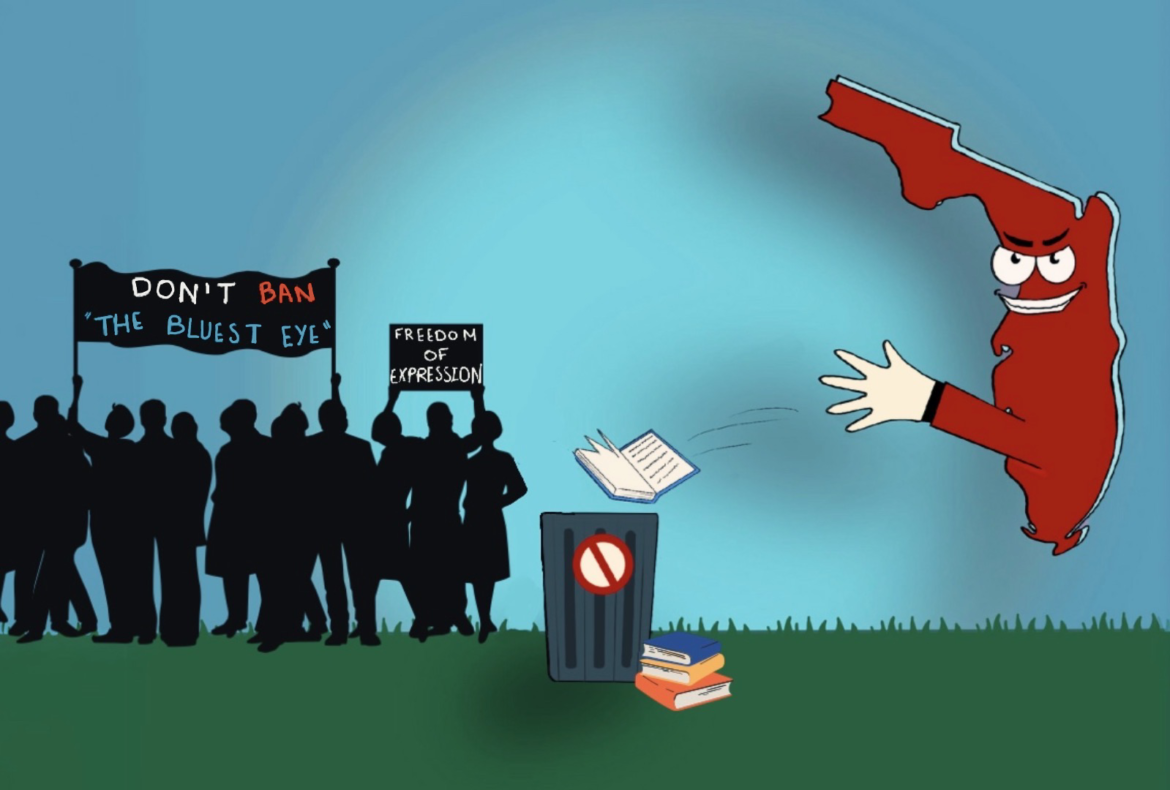

Over the past few years, Florida has made its way to the front of the national stage in terms of conservative policy in education. With Governor Ron Desantis’s campaign for presidency, news outlets around the country have been focusing their attention on the policies that have been enacted under Desantis’s governance. Growing up in Florida the majority of my life, the changes have been jarring. I’ve experienced the shift as legislation such as the Parental Rights in Education (commonly known as “Don’t Say Gay”) and Individual Freedom Acts (commonly known as “Stop WOKE”) have come into law. It started with the removal of our school’s gender and sexuality alliance club (GSA); then the rumours that university majors like African American studies or gender studies would be removed. Finally, the book banning started.

The Democrats and Republicans have consistently held a roughly 50-50 split of votes during presidential elections over the years in Florida. When looking at House and Senate elections, it becomes evident that the Republican party dominates. After Trump’s presidency, this has become much more apparent in Florida’s policies and their effect on schools. Traditionalism and an aversion to open dialogue have become pervasive throughout the state; ideology and law enables this crusade on Florida public education. Proponents of the removal of certain books from schools often cite parents’ rights as justification. This is the idea that parents should have the authority to make decisions regarding the care and upbringing of their children, specifically in schools. Supporters of these mass removals of literature also often claim that it is for the protection of children from “sensitive” content. This definition of “sensitive” remains ambiguous but is typically used to describe material containing what is referred to as “pornography,” concepts like 2SLGBTQIA+ topics, or critical race theory.

The way the government enforces these values in Florida public schools is through legislation. The Parental Rights in Education Act restricts discussion of gender and sexuality in classrooms and requires schools to inform parents of all decisions regarding the care of their students. This results in schools taking extra precautions to avoid discussions that could potentially violate the act. Even children’s books like And Tango Makes Three by Justin Richardson and Peter Parnell, a story about a penguin with two dads, have been removed from schools. These actions haven’t been met quietly though, and specifically in the case of And Tango Makes Three, families have filed a lawsuit against its removal. The Individual Freedom Act has massive ramifications on the permittance of literature in Florida schools. This act claims to prevent discrimination in the classroom by forbidding dialogue that discusses oppression in regards to “race, color, national origin, or sex,” however some argue that its purpose is really to prevent teaching of Black U.S. history and the commonly misunderstood concept of critical race theory. Ultimately it seems that two main themes dominate in the books banned in Florida; according to a study by Pen America, during a 6-month period, over half of the unique titles banned belonged to books that are “about race, racism, or feature characters of color” or had “LGBTQ+ characters or themes.” Other titles that have been banned include Anne Frank’s Diary: The Graphic Adaptation by Ari Folman, Gender Queer by Maia Kobabe, and I am Not Your Perfect Mexican Daughter by Erika L. Sánchez.

Due to the ambiguity of these laws, the Florida state legislature has put school districts in an awkward position. How does one interpret these new rules? There’s little guide as to what is considered “appropriate” for each age group or what material is too “sensitive” for schools. It’s arguable that these laws were written intentionally this way. By creating such ambiguous legislation with major legal ramifications, school districts are forced to decide what is the proper course of action for their schools. In many situations, this results in administrations electing to model a conservative understanding of the new laws. This means playing it “on the safe side” and removing books even when there is a case to be made for its literary merit and benefit to the classroom. On the other hand, administrators have the ability to fight back against these new unjust rules and keep books of literary merit in school libraries.

In my own life, the legislation on appropriate literature material in school manifested in the removal of The Bluest Eye by Pulitzer Prize-winning author Toni Morrison from my school district during my senior year of high school. As a junior, I had read the work for English class and found it to be a really moving and important book to my education. It took the thoughts I had in my head about growing up as a person of colour in the United States and put them into words. I felt seen. Many of my classmates felt similarly, while others felt they better understood this perspective after reading the book. When we received news of the decision to remove The Bluest Eye, myself and two of my classmates scheduled a meeting with our area superintendent and planned a schoolwide protest of the ban. We spoke with local press and attended a school board meeting to voice our opinions on their decision. A few weeks after the fact, the school board reversed their decision and The Bluest Eye was allowed to return to school bookshelves—we had won. This was a victory for students. So often is the student perspective forgotten in policymaking and this was an instance in which we were heard. Moreover, we got to keep a book with important representation for students in the classroom.

The quote that became my motto throughout that fight for The Bluest Eye comes from Toni Morrison herself and it reads, “Don’t let anybody, anybody convince you this is the way the world is and therefore must be. It must be the way it ought to be.” It’s up to us to decide how “it ought to be” and that means taking a stand when important literature is banned. It’s our education at stake and that’s a cause worthy of fighting for. History shows us that those on the side of banning books and conservative censorship are never right, and this is no exception.

Edited by Ailish McGiffin

Hannah Hipólito is in her first year at McGill University pursuing a Joint Honours BA in Political Science and Sociology. She enjoys researching and writing about public policy and culture, especially in relation to education, civil rights, and gun control.