All was never fair in science and sports… until the female body came into the picture. With the 2024 Paris Olympics soon under way, conversations surrounding sex-testing are re-intensifying, making the release of Cat Bohannon’s novel Eve remarkably timely. In the infamous opening scenes of Stanley Kubrick’s A Space Odyssey, a testosterone heavy interaction between two early males marks the dawn of humanity. With grand ambitions and a bold narrative, Bohannon revisits this opening scene with a depiction of an early woman giving birth, followed by a re-telling of 200 million years of evolutionary history that places women, instead of men, at the center of the narrative.

The female body shapes not only what it means to be female, but also what it means to be human. Sex testing as a standard Olympic practice was first introduced in 1950 by the International Association of Athletic Foundation (I.A.A.F). The release of Bohannon’s groundbreaking novel and the rise in popularity of women’s sports preceding the Summer Olympics, work together in an unsuspecting and urgent manner to redefine femininity, history, and science. As Ruth Padawer of the New York Times aptly puts: “No governing body has so tenaciously tried to determine who counts as a woman for the purpose of sports as the I.A.A.F. and the International Olympic Committee (IOC).”

In October of 2023, Bohannon unveiled 10 years of research into a revolutionary revisal of our evolutionary history. Through an epic combination of science and speculation, Bohannon reminds readers that while every human has gestated in a female body, evolution has been framed from a male point of view. Until the 1960s, medical studies were mainly conducted on male participants not solely due to sexism, but due to intellectual issues which manifested into societal problems. Unless scientists are specifically studying the uterus, ovaries, or breasts, women are typically left out of the picture. Science has boasted a ‘sex-neutral’ framework, leaving out women’s bodies due to their unpredictable hormone cycles causing ‘deterrences from the norm.’ Men, on the other hand, provide ‘clean data.’ In all, Bohannon’s novel is a compelling piece which calls for society to pay closer attention to the female body because the more we know about women, the more we know about everybody. The explicit stating of this leads us to think of ourselves in drastically new ways.

There is no other time where conversations surrounding sex-testing are more amplified, than at the Olympics. In 2014, Dutee Chand, one of India’s fastest runners, was preparing to compete at the Commonwealth games in Glasgow – her first big international event since turning 18. Chand’s impressive performance at the prior Asian Junior Athletic Championships in Taipei led the I.A.A.F to note her physique as ‘suspiciously masculine.’ According to them, Chand’s muscles were too pronounced and her stride too impressive for a five feet tall female. Following a series of invasive tests, Chand’s testosterone levels were deemed too high and she was subsequently banned from racing at a professional level.

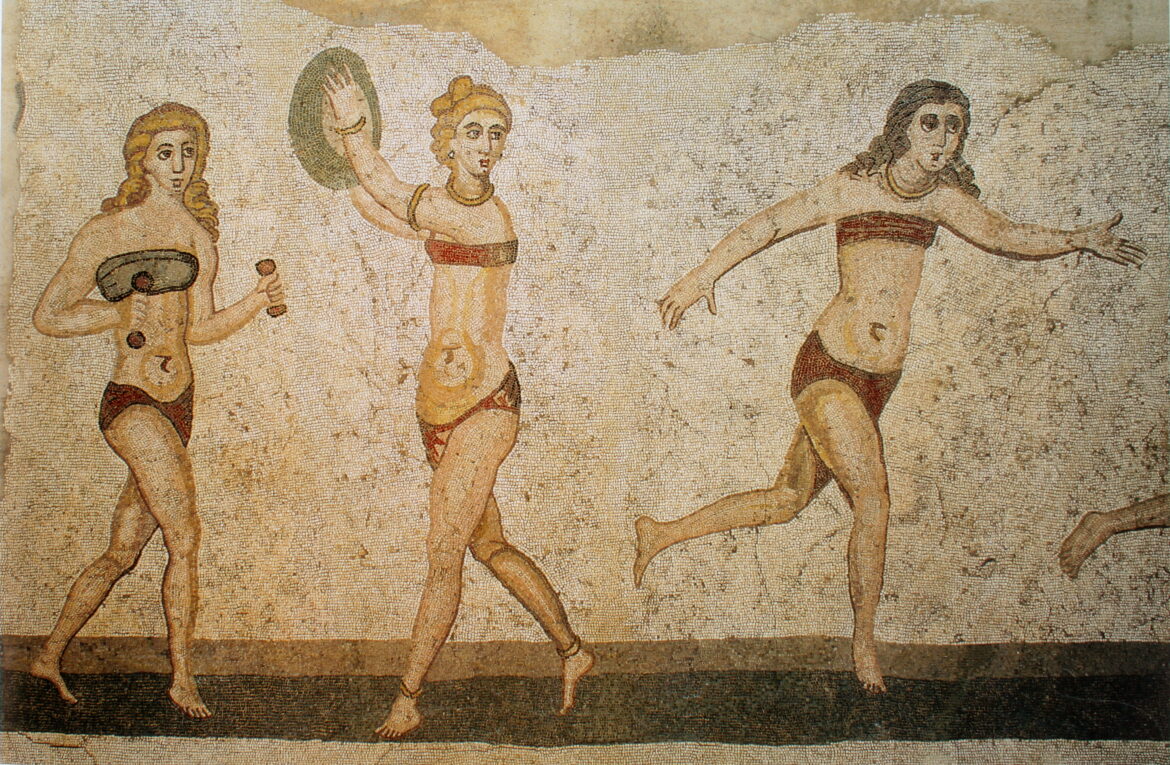

For centuries, sports were an exclusively male domain. Overtime, as women slowly encroached on their territory, the patriarchal structure that stood tall for decades met its formidable opponent. Women were historically discouraged from sport due to the illusory belief that their participation would exhaust their unpredictable hormones and potentially damage reproductive abilities. The growth in women’s sports garnered through increased funding and viewership therefore led to greater anxiety by society; afraid at the thought of women excelling in an arena that men had built for men. It was difficult for society to grapple with the idea that such extraordinary athletes could exist as women. This led to the development of sex-testing protocols in the name of ‘justice.’ In 1966, a mandatory genital check was implemented at international games involving what is now called the ‘nude parade’ where women lined up underwear before a panel of doctors who had the right to conduct closer inspection. The tests later evolved to measuring a woman’s testosterone levels, measuring and palpating the clitoris, vagina, and labia, evaluating breast size and pubic hair, all to be scored on a five-grade scale. Following heavy backlash, they eventually reformed the genital tests in the 1960s to chromosome tests. It was claimed that chromosomes ‘indicate quite definitely the sex of a person.’

Ewa Klobukowska, a Polish sprinter was one of the first women to be ousted due to the more ‘dignified’ chromosome test which showed that she had both XX and XXY chromosomes. At every step of the way, sex-testing has been a humiliating and traumatizing practice, effectively expressing to women that they are not ‘female enough’ to participate in professional sports. It has placed gender into strict empirical measurements, excluding those who do not fit neatly into its criteria.

Later on, the I.A.A.F would acknowledge that there was no reliable scientific evidence indicating that men with exceptionally high testosterone levels had a competitive advantage or that high levels of natural testosterone in women was correlated with impressive athletic performance. These women may have never known their sex development was ‘abnormal’ unless they were tested in such intrusive ways, Padawer notes, or have been barred from competing in world class sports.

One of the leading points Bohannon makes in Eve is that mislabelling the human body has led to disastrous effects in society. Sex-testing at the competitive level is seen as a means of ensuring fairness, but ultimately, it is backed by a male-dominant science. It is a shameful attempt at equity, outing those who fall slightly outside the narrow confines of traditional science. Many geneticists and endocrinologists have pointed out that sex is determined by an evolving confluence of hormonal, genetic, and physiological factors: ‘relying on science to arbitrate the male-female divide in sports is fruitless, because science cannot draw a line that nature itself refuses to draw.’ What we currently believe differentiates ‘male’ and ‘female’ has been heavily skewed by gaps in our intellectual history as Bohannon subtly notes. No governing body yields the right to use science as a shield for patriarchy, exclusion, and humiliation. She argues instead for an inclusive science that is not afraid to investigate all domains whether or not the data is ‘neat.’

The actions of the I.A.A.F and IOC do not go unnoticed. Critics argue that if sport officials were truly concerned about fairness, they would shift their focus away from investigating women’s testosterone levels and instead towards the number of athletes suspected of taking performance enhancing drugs which indisputably interfere with athletic competition. In the past five years, the I.A.A.F has faced a handful of bribery and blackmail charges alongside allegations that they have intentionally dismissed hundreds of suspicious blood tests.

Dutee Chand’s fight to be able to compete professionally has been long and grueling. Fortunately, in 2016 judges concluded that requiring women like Chand to change their bodies in order to compete was ‘unjustifiably discriminatory.’ This was the first time the court had ever overruled a sport-governing body’s entire policy.

In 2021 following a year-long process, the IOC introduced a revised framework on ‘fairness, inclusion, and non-discrimination on the basis of gender identity and sex variations.’ It sought to acknowledge that the IOC cannot set uniform eligibility criteria for all sports, proposing a 10-principle approach instead to assist governing bodies in developing fair criteria. Taking into account social, ethical, and legal considerations, the framework particularly addresses the separation of male and female competition to ensure fairness without excluding athletes based on identity or sex variations. While there is still significant work to be done, this framework marks a progressive leap towards achieving an equitable playing field for those who transcend traditional binary categories.

Sports legislation on the basis of fairness, inclusion, and equity is an ever-evolving landscape. With the 2024 Summer olympics just 5 months away, it will be the first time the IOC’s new framework is tested. Katie Ledecky, Yulimar Rojas, and Rebecca Andrade are a few of the women who stunned the world in the previous Olympic games with their impressive resilience and skill. Will they catch the eyes of the IOC? Female athletes aspire for a future where sports officials prioritize a women’s voice and body over a man’s political aspirations, hoping, as Linda Blade of Reality’s Last Stand notes; “that sports leaders will be honest with scientific data and fulfill their duty as guardians of fair sport.”

The stage is set, its players primed, yet the outcome remains a mystery. As the curtain rises on the Paris Olympics, only time will tell how effectively and honestly the IOC will uphold its promises. What we know for sure, underscored by Bohannon’s Eve, is that women are here, and they will continue to persevere against all odds in the fight for inclusion, justice, and a science that works for all.

Edited by Justine Delangle

Megan Tan is in her third year at McGill University, currently pursuing a BA&Sc in Cognitive Science with a minor in Philosophy. As a Staff Writer at Catalyst Publications, Megan aims to bridge her background in Behavioural Science with International Development as her writing is mainly focused on the Health and Technological dimensions of global political issues. Having grown up in Singapore, Qatar, and Canada, Megan strives to use her diverse upbringing to offer a multifaceted lens through which she examines the interplay of technology, health, and cognitive science.