“Everyone has the right to education. Education shall be free, at least in the elementary and fundamental stages. Elementary education shall be compulsory. Technical and professional education shall be made generally available and higher education shall be equally accessible to all on the basis of merit.”

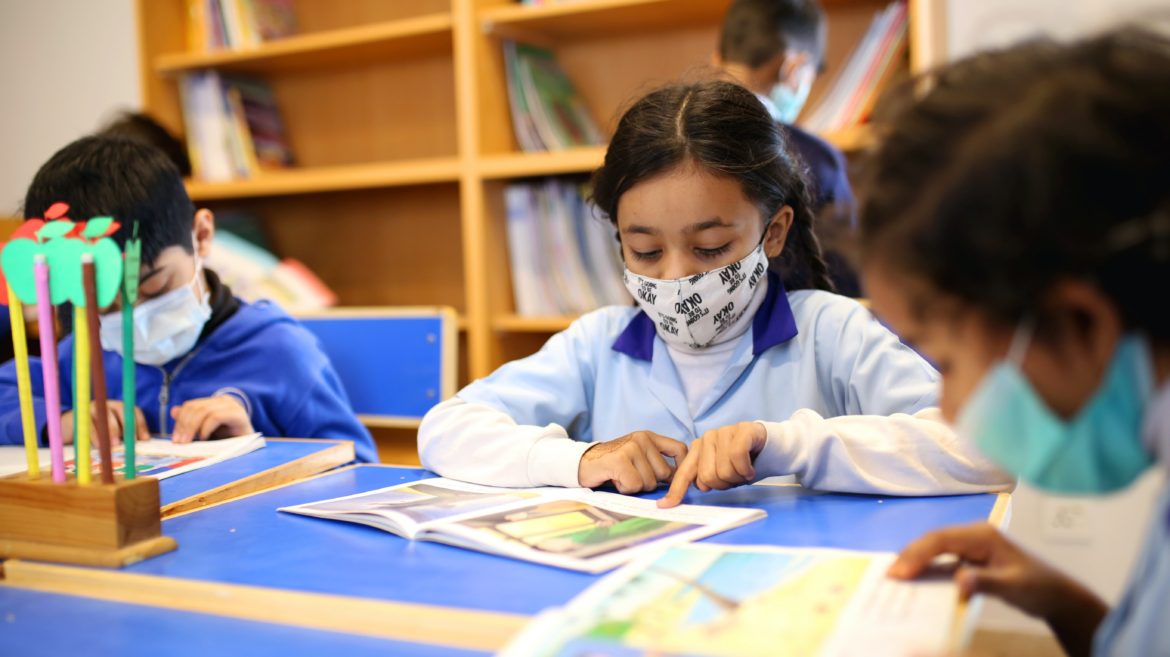

According to Human Rights Watch, by April 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic has led 1.4 billion students across different educational levels to experience school shutdowns in over 190 countries. Since October 2021, transitioning back to some sense of normalcy has been a vicious cycle of adapting to online learning and disrupted attempts to go back to in-person schooling— only to have to resort to remote learning once more. Children— while constantly emphasised in the news as being not likely to experience extreme symptoms and outcomes from Covid-19— have nonetheless been profoundly affected by this pandemic. Not only are educational milestones and opportunities significant, but the socialisation from classroom participation is also deeply important for children’s development. Indeed, many instances of educational inequity have resulted in children from Global South countries not being able to attend school at all.

The disruption to traditional methods of learning extends beyond learning from home while waiting on government regulations to reopen schools in a way that follows each country’s respective epidemiological situation. There is a dimension of socio-economic inequality—which exists particularly in the Global South— that means that approximately a third of schoolchildren, about 463 million children, are unable to access remote learning in any capacity. Within ASEAN countries, it is estimated that school closures have affected 152 million children. UNICEF executive director Henrietta Fore has stated that “the sheer number of children whose education was completely disrupted for months on end is a global education emergency. The repercussions could be felt in economies and societies for decades to come.” Considering that the right to access education is upheld as a universal human right, the pandemic has certainly challenged the application of this right. Factors that expose educational disparities around the world include access to a stable internet connection, having the appropriate devices to be able to tune into remote learning, the potential loss of income on the parent’s side affecting the ability to pay school fees going forward, having a home environment that is not conducive to learning and so forth.

The economic cost of this collective educational loss speaks for itself; The Asian Development Bank (ADB) estimates that developing Asian countries have experienced a financial loss of approximately 1.25 trillion in April 2021. This has the implication that children from these regions are projected to earn 2.4% less annually for their future earnings. The economic risk is not understated and does pose long-term issues for South-East Asia’s economic recovery as their future labour force will have experienced significant disruptions in their schooling, with each country in that region, aside from Singapore, having school closures exceeding 100 days. Having said that, the economic figures must not be prioritised as the only detrimental effect worthy of attention in this pandemic. Social conditions must also be acknowledged to explain why ‘back to school’ is a difficult or near impossible feat for some South-East Asian children after 1.5 years of this pandemic. For starters, the UN and the International Labour Organisation (ILO) found that figures for child labour have increased by a dramatic amount since 2000 due to the loss of income for many disadvantaged families. Without social protection in many South-East Asian countries, national budgets having to be readjusted and the volatile economic conditions, UNICEF predicts the trend of child labour to only increase to supplement lost income for their household’s future.

Many have also overlooked how gender is a critical factor in these academic equalities. In fact, UNESCO estimates that 11 million girls will not be able to return to school post-pandemic, a situation that is all too real in South-East Asia. Pandemic conditions have made it so that the many girls who have dropped out of school—whether it be to help with household chores, or to pick up extra jobs to earn income— are also at a high risk of being set up in underage marriages to supplement income and of becoming victims of domestic exploitation and sexual and physical abuse. Furthermore, lack of contraceptive education could lead to unwanted pregnancies and other complications, which would ensure that these girls would be unable to return to school post-pandemic. These circumstances have grave repercussions in shaping how future generations of women approach their right to education. If it is not prioritised, it will significantly set back strides made in educational equality in these regions.

This crisis of education has undoubtedly set many South-East Asian countries back years in terms of financial and social growth. ‘Catching up on missed learning’ is not enough for some countries. The educational systems from countries of the Global South have always been broken and it is only in these extraordinary circumstances have we been able to see the extent of its deep-seated problems. It is not enough to return back to pre-pandemic schooling, especially when 10 to 16 million children globally do not have this choice. The digital divide that has plagued schoolchildren since the beginning of the pandemic is very real, but it is only the least of the issues that children have had to face in terms of access to education. As seen through this article, perhaps the larger issue is that without the prioritization of education—as championed in our social discourse— children from the Global South are vulnerable to so many situations which will affect the immediate outcome of their futures.

Edited by Olivia Shan

Sokhema Sreang is in her last year at McGill University and she is pursuing a major in International Development and a minor in Sociology. She has joined Catalyst as a staff writer and is particularly interested in the politics of developing countries, social protection and social change.