Post-Scarcity economics considers a future system of production where goods can be produced cheaply and in abundance using minimal labour such that there is more than enough for everybody. This field has placed heavy emphasis on the role of automation and artificial intelligence in transitioning to a post-scarcity world — for example, through the usage of self-replicating machines such as those researched by RepRap. Even over a century ago, Karl Marx mentioned in his notes that automation could lead to an era where the necessity of labour would be minimal, and people would be free to pursue academic and creative endeavours. While this situation could doubtlessly alleviate the needs of many, it must be considered that the path to getting there could create issues in the relationship between the Global North and the Global South. This can be seen by examining the nature of offshoring in international trade and the pathways presented towards development in the Global South.

Already there are criticisms of this path to post-scarcity from other fields. Some environmental activists have argued that this state of production would be taxing on the environment and could drive up the cost of raw materials and energy due to increased demand. While these criticisms are no doubt worth considering, they are out of the scope of this article. Further, developmental economists would argue that the reliance on such technologies would end up increasing the economic divide between the Global North and the Global South. This argument is based on the Romer Model, which theorizes that countries with better technology grow at a faster rate than countries with less-advanced technology. As such, the difference in the two countries’ standards of living would increase over time. Thus, assuming that advanced economies in the Global North were the first to use such automated technologies, we would see a further divergence in the standards of living between the Global North and the Global South.

This latter argument already posits a worrying trend. However, there are even further consequences to consider that could compound these effects. These relate to the current structures in place in the global economy. Currently, nations in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) are responsible for the largest shares of foreign direct investment (FDI) outflows in the world. Much of these flows are directed toward the Global South, either to open a new plant, or acquire part of a firm. This means that many of the large firms that exist in the Global South are owned/controlled by entities in the Global North.

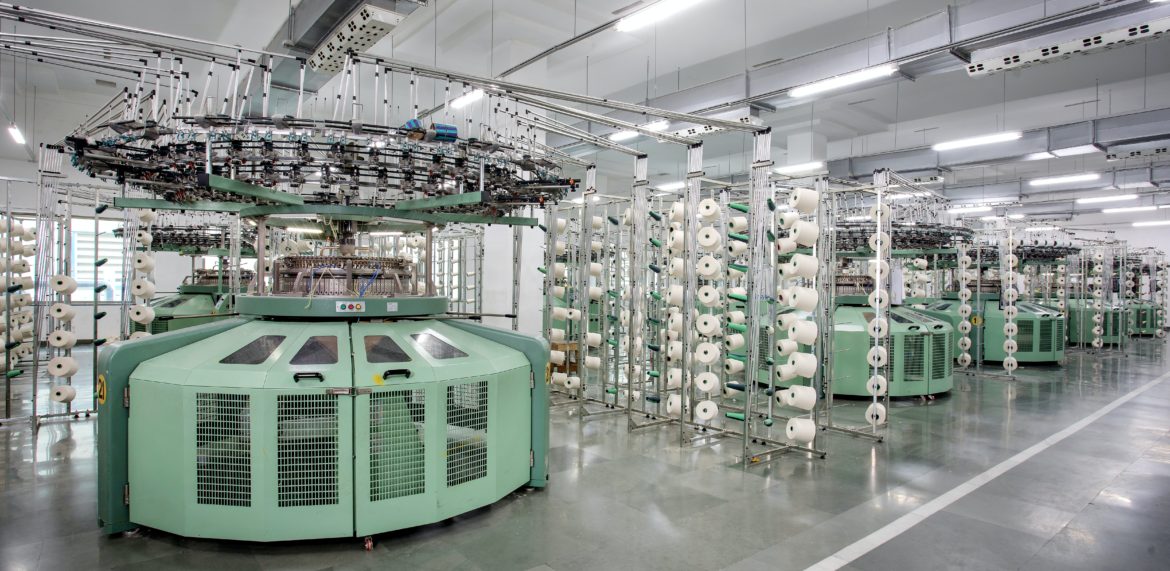

How does this relate to development? Consider the clothing industry, which uses cheap labour in the Global South to produce goods. While these production centres are known for their poor working conditions and low wages, trade economists often argue that this is better than the alternative of having no production centres in the Global South. As evidence of this, they point to the fact that so many people are willing to work in these conditions, and so working there must be preferable to the alternatives that would otherwise exist. Essentially, trade economists argue that it is acceptable that the main pathway for a poorer country to economically develop is through the capital provided on the terms of a firm in the Global North. By introducing automation and artificial intelligence to this situation, it can be seen that claim becomes unsustainable.

First, one should consider the decisions that guide FDI flows. FDI comes in two types: vertical and horizontal. Vertical FDI refers to a firm breaking up its production process and relocating certain steps to different areas around the world. It usually involves taking a process that requires a large amount of labour relative to capital and relocating it to somewhere in the Global South. Horizontal FDI refers to a firm opening a new centre in a different location where the entire production process is replicated. Usually, this is done to get closer to a consumer base and is mostly done between Global North states.

Focusing on vertical FDI, one must understand the reasons for why a firm would decide to undertake such an investment. Countries in the Global South tend to be more labour abundant, and consequently, can more cheaply produce goods that require relatively more labour than capital. So, if a firm sees that the cost of opening a new plant and splitting up production is less than the amount they would save by utilizing the labour there, they will do so. What does this mean with respect to automation? If a firm is now able to conduct the labour-intensive process using automated and self-replicating capital — that is, without needing labour — then they would not be incentivized to use vertical FDI in the Global South, since the labour incentive would no longer be relevant.

A firm would then have incentive to move the production process back to the Global North due to the competitive advantages available. These refer to factors such as abundant human capital, energy access, research and development centres, quality infrastructure/transportation, and access to technology among others. These are all much more abundant in advanced economies than less-advanced ones. Thus, the argument that countries in the Global South should develop via the opportunities provided on the terms of firms in the Global North is unsustainable. These firms will gladly relocate if they find advantages to, taking their capital and the jobs they provide with them.

Still, ignoring the factor of competitive advantage, would it be possible for there to be enough technology transfer to even the playing field? Could these automated technologies be concurrently employed in the Global South? A contemporary model that incorporates technology transfer in development is the modern Flying Geese model. It argues that one economy can ‘lead’ nearby economies to development by passing off less-advanced industries as it progresses towards more capital-intensive ones. Whenever the lead economy gains a comparative advantage for a new, more-advanced industry, it passes the previous industry to the countries ‘behind’ it. These ‘behind’ economies then pass their previous industries to the ones behind them, like the V-shaped migration pattern of geese. Through this pattern, countries develop into more sophisticated economies.

The modern Flying Geese model states that this form of industry transfer also brings with it more-advanced technology. This is done through multinational corporations utilising FDI to relocate plants. This clearly brings back the issue at hand. Further, this technology transfer occurs in a stepwise manner. Industries are passed down one-by-one as the lead economy progresses. It is not a sudden jump toward the newest, most cutting-edge technology available. By the Flying Geese model, even if FDI is ignored, a country would still have to go through all the ‘stages’ leading up to the advent of the automated capital to reach it. Thus, when technology transfer is incorporated into the analysis, it is seen that automation would still benefit advanced economies first and would not naturally be brought to less-advanced economies since there would be no incentive to use FDI to relocate to these countries.

While automation and artificial intelligence could pave the way for a post-scarcity world, there are still issues to consider. Asides from environmental issues and the Romer model’s predictions, one can see that such technology would dramatically alter FDI flows. This would lead to firms relocating parts of their production process away from the Global South and back to advanced economies if they can save more money by taking advantage of labour-free processes. As such, the model of economic development posited by many trade economists would no longer apply, as the opportunities provided by vertical FDI in the Global South would be removed. Clearly, the path toward post-scarcity is one that must call into question the current structures of the global economy.

Edited by Isabel Muñoz Beaulieu

U3 student at McGill majoring in International Development Studies and Computer Science. Interested in economic development, indigenous issues, sustainability, and criminal justice reform. In my free time, I’m passionate about fitness, baking, music, and fashion!