In the past month, Peru has descended into chaos. Beginning after the impeachment of President Pedro Castillo by the Peruvian congress, protesters across the nation have risen up, demanding a change to the political status quo, which has the legislative branch wielding disproportionate control over the country. In the weeks following Castillo’s removal, there have been numerous clashes between protesters and police, as well as massacres committed by the Peruvian government that, according to some, constitute genocide against the Indigenous people of Peru.

Peru has a turbulent political history dating back to the 1990s when it was ruled by Alberto Fujimori. Fujimori was a right-wing dictator who remains contentious in Peru to this day. Although his regime committed human rights abuses, he is widely credited with developing the Peruvian economy under a neoliberal model, which, although increased productivity, resulted in widespread inequality. Pedro Castillo was elected to the presidency in 2021 in what was seen as a major upset to Peruvian politics. At the time, Castillo was relatively unknown and Peru had been governed by various neoliberal politicians following Fujimori’s footsteps. As such, when a firebrand, left-wing populist beat Keiko Fujimori, Alberto Fujimori’s daughter, it was considered a radical shift in Peruvian politics.

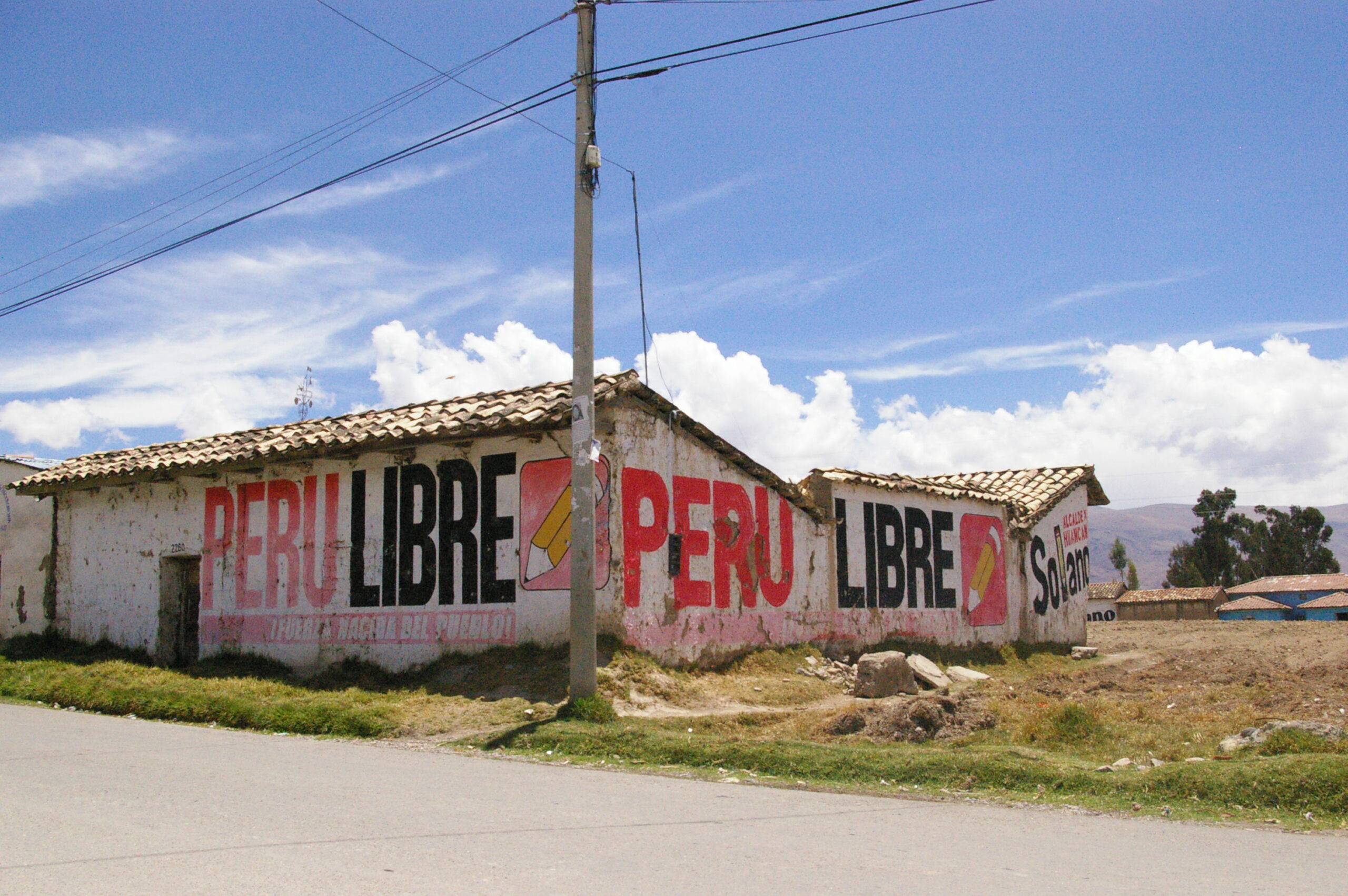

Castillo had run on two primary issues: replacing Peru’s constitution and shifting towards nationalization of resources and investment in public services. The current constitution of Peru was written by Alberto Fujimori during his time in office and gives the legislative branch wide-reaching powers, including the ability to impeach the president simply with an arbitrary declaration of moral incapacity. In the time since Fujimori was ousted from power, congress has liberally utilized this power, impeaching any president who tried to shift Peru away from Fujimori’s vision. As such, from the very moment Castillo became president, he faced opposition from the media, congress, and the system itself. With congress obstructing everything Castillo attempted to pass, it became clear that nothing the Peruvian people desired out of him would be accomplished. Proposals to reform the constitution were shut down by congress, and whenever Castillo attempted to rule by presidential decree, the media painted him as a tyrannical autocrat. In a situation like this, there was no way for Castillo to fulfill his mandate.

During his time in office, Castillo accomplished virtually nothing. In his year as president, congress attempted to impeach Castillo three times, with the first two failing and the third one finally removing him from power. In the time leading up to the third impeachment vote, it was clear that there was a reasonable chance of success. As such, in the face of impending removal from office, Castillo attempted to dissolve congress, hold new elections, and create an elected constitutional convention to draft a new constitution. This did not work. In his attempt to pre-empt the coup from congress, Castillo had not secured any support from the military, police, or media, all of which that are vital to securing political control yet were firmly in the hands of the neoliberal establishment. As might be expected, congress responded to Castillo’s attempt at dissolving them by impeaching him, this time successfully, and arresting him.

Although Castillo had grown widely unpopular during his time in office, wielding an approval rating of around 20% at the time of his removal, congress was even more unpopular. After Castillo’s impeachment and arrest, protests erupted across Peru demanding, among other things, his release, new elections, and the establishment of a constitutional assembly. To these people, Castillo represented a rejection of the neoliberal status quo. Though the people of Peru were not impressed by Castillo’s time in office, congress’s decision to remove and imprison him turned Castillo into the figurehead of a popular uprising. As such, the protests could be better characterized as anti-congress rather than pro-Castillo.

Since protests began, the government has frequently clashed with protestors, yielding deadly results. The government under Dina Boluarte, who succeeded Castillo after his removal, has refused to bring forward elections. Dozens have died within the past month, with the Peruvian Army and the National Police outright massacring protestors on two separate occasions. First, on December 15, the army opened fire on a group of protestors in Ayacucho, killing 10 and injuring 61. Then, on January 9, the National Police shot at protestors in Juliaca, with 18 being killed and over 100 wounded. In the aftermath of these events, the attorney general of Peru opened up an investigation into the Boluarte government for genocide and aggravated homicide. The genocide charge is especially important, as the Peruvian government has been accused of targetting Indigenous communities and protestors.

Many left-wing leaders across Latin America have been quick to denounce the government of Dina Boluarte and express support for Castillo and the protestors. Among them, ex-Bolivian President Evo Morales, who issued a statement in the aftermath of the Ayacucho massacre stated, “we join the cry of defenders of life and Human Rights to demand that they stop the massacre of our Indigenous brothers in Peru who demand respect for their vote and a democracy that represents them. No government staining its hands with the blood of the people is legitimate.” However, this stance has not been widely adopted, with Canada and the United States expressing support for the Boluarte government in the wake of the massacre of Indigenous civilians. In recent weeks, protestors have begun to converge on the capital of Lima in what they call the Toma de Lima, or the Taking of Lima, where still more protestors have died facing security forces. As Peru continues through this crisis, it remains unclear what the end result will be.

Edited by Alyana Satchu

*This was initially on February 6 but was edited for minor grammatical changes. No content was changed.

Alexander Morris-Schwarz is a third-year student at McGill University where he is majoring in Political Science with a minor in Communication Studies. Alexander is currently a staff writer for Catalyst and he is interested in international relations and imperialism.