The COVID-19 pandemic has undeniably hit the global economy hard. Unemployment, reduced consumer spending, and increased government spending, are all main contributors to the faltering domestic and global economies. As we attempt to look ahead, we turn, somewhat helplessly, to those with greater authority.

Governmental responses to the pandemic have been varied and highly criticized. As the search for a vaccine picks up, and its immeasurably high demand drives cutthroat competition, we see the different ways in which countries and coalitions have approached this potential long-term solutions to the situation.

President von der Leyen of the European Commission, the executive branch of the European Union, was the first to propose the idea of an internationally coordinated response to the pandemic. Following her call for joint action, von der Leyen approached various global health entities and philanthropists, and this effort quickly led to the formation of the Coronavirus Global Response with nations such as Canada, France and Germany joining the initiative. To date, this group has pledged to provide more efficient and effective testing methods, develop treatments that minimize symptoms, and find a vaccine. The alliance raised almost sixteen billion euros from the end of April to the end of June 2020, and has continued to mobilize their agenda through funding provisions and follow ups with various pharmaceutical companies and vaccine manufacturers. Most importantly, the Coronavirus Global Response has affirmed itself as a united front committed to the universal and inclusive access to the vaccine, once it is accessible.

The group has also extended its efforts to cover broader health issues. For example, it has pledged 300 million euros to Gavi, a renowned vaccine alliance, over the period 2021-2025. This sum is directed to the initiative to immunize 300 million children against infectious diseases prominent in developing areas of the world, such as HPV, measles, and polio. The potential for the Coronavirus Global Response to emerge as a leading health coalition, on both large and small scales, stands as a silver lining amidst these trying times.

This picture of composed and cooperative action between nations takes on quite a different character in the United States. American decisions regarding development and international distribution of the vaccine have been extremely unclear. Although President Trump claims that the US is open to partnership, especially concerning the circulation of the vaccine, many of his actions directly contradict these seemingly inclusive claims.

For example, America’s recent refusal to participate in COVAX, the Covid-19 Vaccine’s Global Access Facility, displays a decisive resistance to work with other countries. COVAX includes almost 170 nations, and has been provided with 400 million euros by the Coronavirus Global Response. However, even this backing could not entice the US to abandon its isolationist approach to recovery. The Trump administration went so far as to offer Curevac, a German medical company, large sums of money in exchange for exclusive access to their product. This request was originally turned away, but, shortly after, the CEO of Curevac, Daniel Menchilla, unexpectedly left the firm and was replaced by Ingmar Hoerr, the founder of the company. Menchilla, originally a US citizen, was then invited to the White House to discuss strategies “for the rapid development and production of a COVID-19 vaccine with Trump, vice-president Mike Pence, and members of the White House coronavirus task force.” The actions of President Trump and his coalition have spoken louder than their words. The clear inconsistencies in his claims have created skepticism about the potential decisions that the US government will take if they are to discover an effective vaccine before other nations.

The United States has invested close to 11 billion USD in a few select pharmaceutical companies, as part of Operation Warp Speed, an initiative aiming to provide upwards of 300 million doses of the vaccine by January 2021. The pharmaceutical company Novavax was the biggest recipient of this investment package, receiving 1.6 billion dollars “to cover testing, commercialization and manufacturing” of the vaccine. The funding also paved the way for a boost in the stock market, with Novavax’s stock surging by 35% immediately afterwards. Other noteworthy companies given hefty government investment include Johnson and Johnson, Moderna and Astrazeneca.

The distinct formats of the EU and the US’ efforts to develop a COVID-19 vaccine raise important questions about what the outcomes may be. How will either group distribute vaccines? Furthermore, this brings forth questions of the ways in which economies will work towards long term recovery. How will specific ways of administrating and distributing the vaccine impact the rebuilding of either the American or EU economy?

In reality, if the US were to discover a vaccine first, their heavily globalized economy might likely force the eventual widespread distribution of the vaccine. Assuming that the US hopes to prevent long-term economic scarring and rejuvenate their economy, an isolationist course will likely hinder, not help, this outcome. Moreover, many of the pharmaceutical companies the US has funded as part of Operation Warp require international resources. Novavax, for example, bases particular manufacturing operations in Sweden and the company is looking to create more plants in Europe and Asia. Overall, the dependency of the American economy on exports and the use of other international services might make withholding the vaccine extremely costly for the US.

Additionally, in comparison to the more collaborative Coronavirus Global Response, the layout of Operation Warp Speed poses striking moral concerns. In the midst of a global pandemic that has cost many lives, it would be safe to assume that unity might fare us better than derision.

Even within the US, the growing economic inequality and limited government aid have posed moral concerns for citizens. The ease with which the US government has neglected its most vulnerable populations during the course of this crisis casts doubt on the intention behind its future extension of the vaccine. The US’ dismissal of global collaboration as well as the potentially unequal distribution of an American vaccine reduces the US’ authority as a global leader. President Trump has cast doubt on the reputability of the World Health Organization. His personal hostility and scapegoating of the organization’s operations have led the country to pledge withdrawal from the WHO by 2021.

While there have been recent advances made in vaccine production efforts by Pfizer and Moderna, one should note the inequitable distribution of these: 80% of the Pfizer vaccine has been bought up by rich countries which house only 14% of the world’s population. The unfortunate reality this statistic reveals is unsettling. However it cannot be said to have been unexpected. There have been several roads taken by governments towards the discovery of a COVID-19 vaccine and this variation potentially carries long lasting effects. Throughout the pandemic, countries have struggled between notions of self-interest and collaboration. As we push to make our way through this uncertain time, it is unclear which of the two will prevail.

Edited by Ines Navarre.

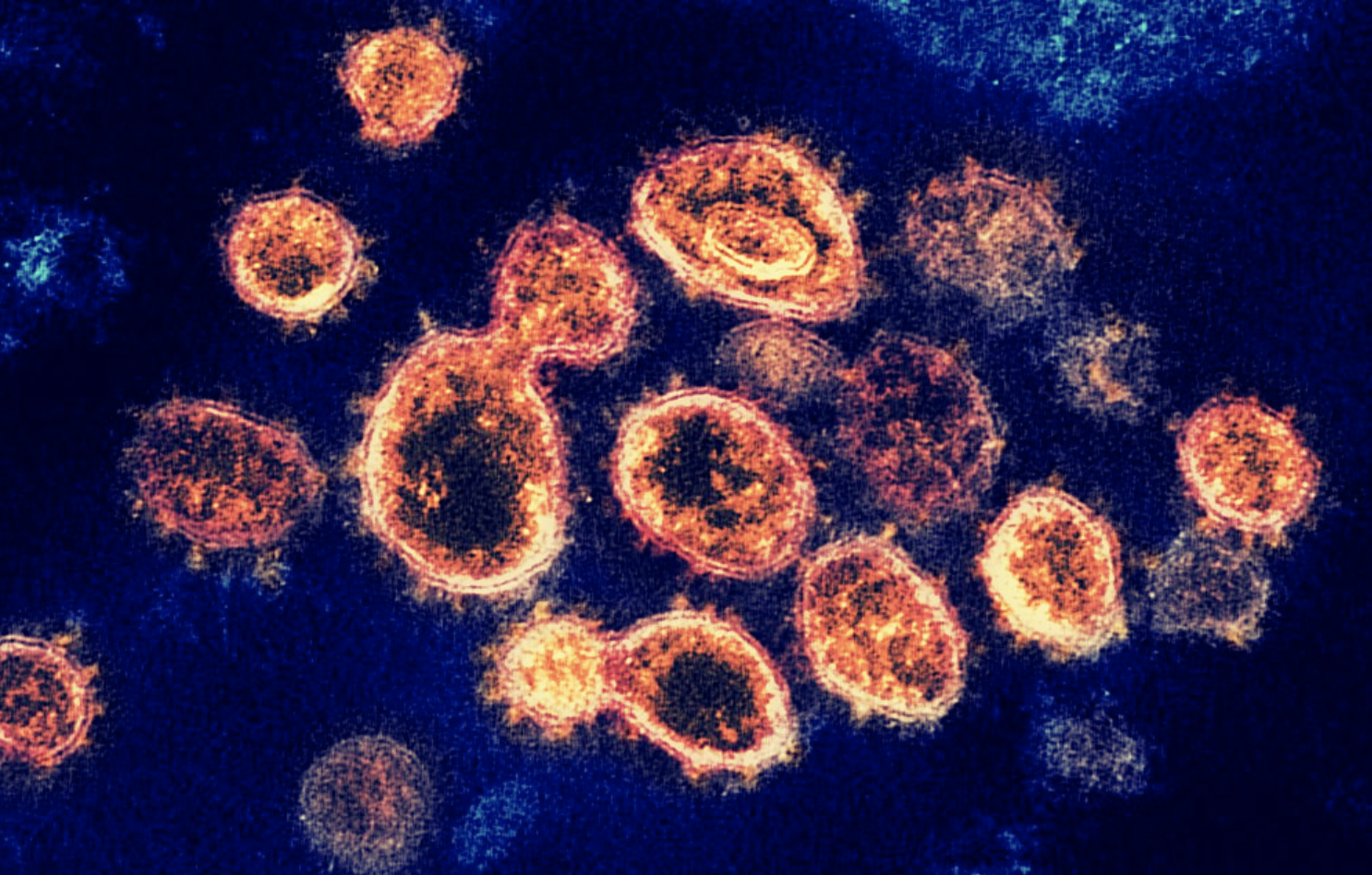

Photo credits: “SARS-CoV-2 (µ-IMAGE)” by Quapan taken on May 21st, 2020, licensed under CC-BY 2.0. No changes were made.

Misbah Lalani is a first year at McGill University, pursuing a bachelor’s in honours international development studies and industrial labor relations, with a minor in social entrepreneurship. She is serving as a staff writer for Catalyst and is particularly interested in economic development and market conditions in Middle East.