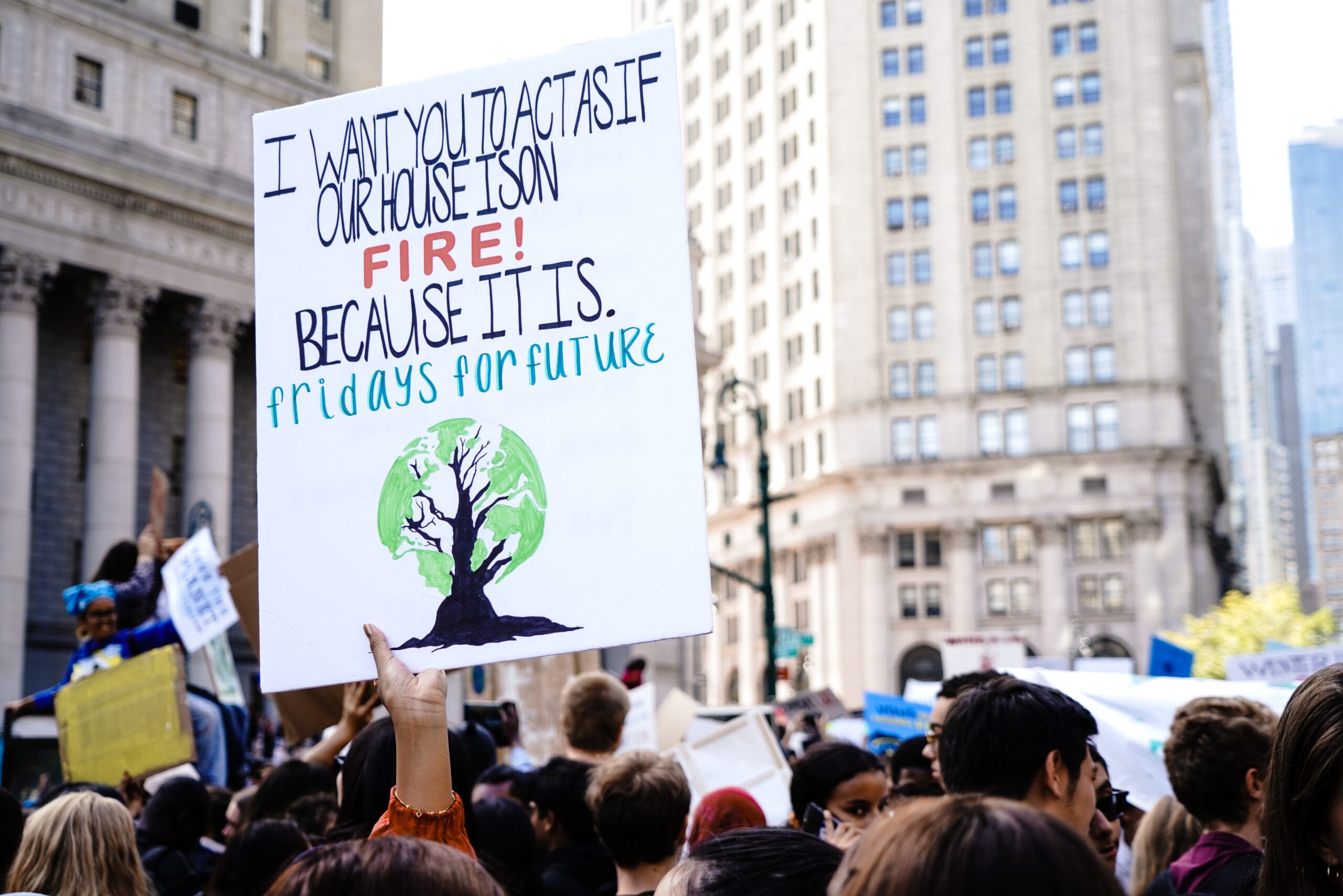

Greta Thunberg is the most striking example of recent climate activism. At only fifteen years old, Greta started protesting in 2018 outside the Swedish Parliament in an attempt to change the minds of international leaders and ordinary people. What began as a small campaign turned into a global movement. Since then, climate activism still occupies an important place in society today as the effects of climate change are being significantly felt. For the ninth volume of its 2023 International Tour, the International Ocean Film presented six short films around the theme of ways to fight for climate activism. “The Power of Activism” (2022), one of the six films, explored the monetary value that can be used and brought forth to help fight climate change. The interesting angle brought to light by this film raises important questions regarding whether climate activism can succeed without monetary value and whether it can generate financial value. Where does this monetary value come from, and are there possible conflicts between profit and the ethics of the environment sector?

Climate change activism has often been framed as costly for businesses. Indeed, climate awareness and campaigns have led to restrictions or bans on the sale of certain goods, which have a high negative environmental impact. For instance, the partial ban of F-gas by the European Union in 2014, a product found in fridges or previously found in hair spray and air conditioning units. These gasses drastically impacted the ozone layer and exacerbated the effects of global warming. But a ban on a product inevitably affects sales and means that the manufacturers suffer from losses. Another reason why climate activism is costly is that ecological transition requires important financial investment. Indeed, the UN projected that 4 billion dollars of investment a year in renewable energy would be necessary to achieve net zero emissions by 2050. However, governments and industries are still reluctant to finance these efforts. Today, progress is slow, and the world still uses non-renewable energies. The global Energy Transition Index (ETI) scores of the World Economic Forum (WEF) show only a ten-percent improvement in the report published in June 2023, meaning that countries are not on the path to achieving net-zero emissions by 2050. In “The Power of Activism,” the three women Madison Stewart, Alice Forrest, and Jordyn de Boer portrayed in the film also believed that their climate-friendly businesses could not generate much revenue and that there was an inevitable trade-off between economic value and social value. This was disproved by an actuarial economist missioned to calculate the financial value behind their projects. She showed that long-term and short-term monetary gains could benefit the community if these projects were implemented. Achieving even global gains for those projects implemented on an international level.

This concept is not new. This paradox refers to a well-known debate between conservation and development and finding a way to balance both. Indeed, the “Bottom of the Pyramid” concept originates from C.K. Prahalad and Stuart L. Hart’s article published in Strategy+Business (2002). This concept concludes that the world is divided into an economic pyramid with the wealthy few at the top and billions of aspiring poor at the bottom and that market opportunity is actually at the bottom of the pyramid rather than at the top. In other words, businesses have a much bigger incentive to do business with people with low incomes or people experiencing poverty and help them to improve their lives for two reasons. The bottom of this economic pyramid hides a significant market, business, and development opportunity for companies to make a profit, even if it requires companies to focus on innovation and change their business model and product content. This change is often naturally more sustainable and eco-friendly since the goal is not to create cheap products of poor quality. The second reason is that focusing on the bottom of the pyramid will reduce inequality by creating better access to products and services for everyone and have other far-reaching consequences, such as helping solve political chaos, inequality, and environmental issues. This philosophy is already used by several groups, such as Group SOS, as an inclusive business initiative.

Similarly, in 1994, John Elkington coined the phrase ” The Triple Bottom Line” theory to define the goals business should focus on: people, profit, and the planet. This was an attempt to encourage companies to think about their social and environmental impact as much as their financial performance. Although this concept has not entirely succeeded in changing corporate behaviours and received some criticism, it is incorporated into business practices by some investors using Environmental, Social, and Governance data (ESG) for investment decisions. Therefore, investing in environmentally sustainable projects is crucial, but climate mitigation projects can also, in turn, generate profit.

The issue, then, is whether economic gains can conflict with the original ethos of the project. A problem that has not yet been discussed at great length in the literature. However, this problem is perhaps similar to another more common example involving supermarkets. Indeed, initially, supermarkets were created for the purpose of accessibility and allowing a wide range of people to access a wide range of goods. Over time, as supermarkets became multinational brands, they have been the source of another problem. To remain competitive, supermarkets lower their prices, sometimes making it hard for local farmers and producers to sell their goods. This was, for instance, the case with the price of milk in France no later than last year.

Similarly, this led brands to compete for consumer attention to push them to purchase their goods not because of the quality of the product but rather to generate more revenue for companies selling their products in supermarkets. As a result, what started as a social project and a solution to a social issue turned into a problem itself. Whether talking about supermarkets or environmental projects, it is important to find a balance between the efficiency of the project, meaning finding a way to generate revenue and preserving the project’s guiding principle. If not, the project could eventually become the source of issues we can not yet foresee.

Overall, the film shows that activism has important social and economic value that benefits the project managers and the community in which these projects are implemented. Activism is a global effort, and actors from all different backgrounds must help one another, policymakers, NGOs, and companies. Secondly, there is a market for climate activism on several levels. However, there must be a balance between ethics and profit so that business goals align with the project’s ethos. Otherwise, we might not be able to reach the targeted climate goals.

Edited by Sabrina Nelson and Ruqayya Farrah

Victoire Thierry is entering her third year at McGill university studying International Development and Political Science. She is a first-time writer and her interest include sustainability, migration and international relations.